|

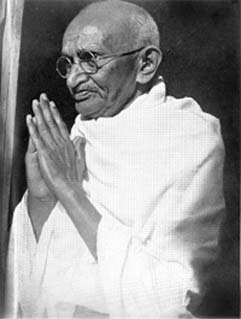

Mahatma Gandhi and the Principles of Satyagraha/Truth-Force and Ahimsa/NonviolenceMahatma Gandhi, Life and Teachings (Compiled in 2000 by Timothy Conway, Ph.D.)

Mahatma (Great Soul) Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) stands as one of history’s greatest heroes of “engaged spirituality,” a spirituality that is active within the world to help heal injustice, hatred, pettiness, fear and violence with justice, loving-kindness, equanimity, courage and nonviolence. In India, he is reverently and lovingly named “Bapu” (Father) and is officially honored as “Father of the Nation,” with his birthday on October 2nd commemorated each year as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday. The United Nations General Assembly on June 15 2007 unanimously adopted a resolution declaring October 2 hereafter to be the International Day of Non-Violence, in Gandhi's memory. Mohandas K. Gandhi was born Oct. 2, 1869 in Porbandar, India, on the west coast of Gujarat, to a rather wealthy family of the vaishya merchant-caste and Vaishnava religious affiliation (worshipping Lord Vishnu). His saintly, austere, religiously inclusive young mother Putlibai and his equally-devout nurse Rambha were major spiritual influences on him, as was his self-sacrificing father, Karamchand, an older man serving as prime minister of the small princely state of Porbandar. Some years later, Mohandas would also be deeply inspired by the illustrious Jaina poet-sage and polymath savant, Rajchandra (“Raychandbai,” 1867-1901). Mohandas, happily wedded to Kasturbai in an arranged marriage at age 13, had to leave his wife and infant son six years later (four years after his father's passing) to study law in London, where, among other things, he became a staunch vegetarian. Returning to India in 1891, his lack of success in establishing a legal career led him to take up a case and begin to practise law at Durban, South Africa in 1893. Reading the Bhagavad Gita Hindu scripture and the social gospel and pacifist message of “love thy enemy” and “turn the other cheek” from Jesus in the New Testament, along with Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You, and Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience, all inspired Gandhi to launch a movement of nonviolent, peaceful resistance against the oppressive government of South Africa and the widespread bigotry and racial injustice of that society against darker-skinned people. His success in founding there the Natal Indian Congress, his weekly newspaper Indian Opinion, and a widely-distributed pamphlet he wrote in 1909 (Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule) paved the way for his return to India in 1915, where he came to the attention of the country’s political class and multitudes of pious souls who began to regard him as the political and moral leader of India in its long road to Independence. It was not a smooth start: Gandhi was loudly booed and rejected by many VIPs and their sycophants at a crowded political convention hosted by the theosophist Annie Besant in February 1916, when Gandhi in his speech dared (in his humble, soft-spoken way) to suggest self-criticism, mass education, abandonment of greed, and trust in God as the way to success. Fairly soon, however, Gandhi became one of the most charismatic figures in the Indian National Congress, and a friend to India's multitudes through his espousal of numerous causes dear to agrarians and simple laborers, who comprise the majority of her population. A key element on the road to India's Independence was not only Gandhi's launching in 1921 of the movement of non-cooperation with the British, but the willingness of the exemplary Gandhi and his comrades to go to prison many times through peaceful, courageous acts of civil disobedience, like the famous Dandi march to the sea in 1930 to make salt against the British ban. Another major element in the campaign was the radically simplified, rustic, yogi-like lifestyle of Gandhi and his colleagues. As he had done with his Phoenix Farm (1904) and Tolstoy Farm (1910) vegetarian ashram-communities in South Africa, so in India he set up the Sabarmati agrarian ashram near Ahmadabad in 1916 and then the Sevagram model village in 1935 in the Wardha district. Here he lived between his widespread traveling, campaigning for justice, incarcerations by the British, speaking to the masses, and prolific writing of tens of thousands of letters (many of them dictated through his secretaries), hundreds of newspaper essays and editorials, several pamphlets and a few books, including his famous autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, begun as a serial for a periodical in 1925 and published in 1927/9, describing his activity up to 1920. He also founded in 1919 the weekly papers Young India in English and its Gujarati edition, Navajivana, renamed in 1933 Harijan and Harijanabandhu for the "children of God," as he lovingly named the scorned outcaste "untouchable" peoples of India (many of whom today prefer to call themselves by the more neutral, nonreligious term "Dalit"--suppressed people). Sabarmati and then Sevagram became, as scholar Iain Raeside notes, "part school, part refuge, but chiefly the headquarters of a powerful movement for independence, for peace, for equality between Hindus and for the tolerance of other religions upon whose hymns and prayers Gandhi would draw freely for his services and for countless moral homilies, spoken and written." As integral to his voluntary simplicity and independence campaign, Gandhi inaugurated the “home-spun” cotton-spinning and weaving industry as a way of inspiring India’s people to become, as far as possible, economically self-reliant and free of the disfranchising colonial power of the British Raj.

The years rolled on.... Gandhi's wife and partner in the great work, Kasturbai, died in prison on Feb. 22, 1944, with the Mahatma at her side. World War II was raging. When the Allies finally won the war, Gandhi, who had graciously backed off a bit during the war years on demanding that the British "Quit India," resumed the nonviolent struggle for Swaraj. Upon his return to India back in 1915, Gandhi had organized poor farmers and labourers to protest against oppressive taxation and widespread discrimination. Soon after assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress, Gandhi had led nationwide campaigns for mitigating poverty, for liberating women, for brotherhood and respect among differing religious faiths and ethnicities, for an end to untouchability and caste discrimination, and for the economic self-sufficiency of the nation. But above all his struggle had been for Swaraj, "self-rule," the independence of India from foreign domination. The dream of Independence for Mother India was fulfilled when the British occupational forces finally and quite amiably left on August 15, 1947, a landmark event that triggered numerous national liberation movements in other countries around the world (some of which would be ruthlessly toppled by the Soviets or by the USA). It was Gandhi’s self-sacrificing spirit and self-imposed, near-lethal fasts, and the moral pressure exerted thereby, which then brought a mitigating, even healing influence upon the horrifically vicious pogroms by Muslims against Hindus and then Hindus against Muslims within a few weeks after Independence when the country fell apart through political-religious rivalry and petty suspicions. The country would be partitioned later in 1947 into a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan. Gandhi, who had reluctantly acquiesced to the idea of partition, had for years earlier expressed opposition to the idea, but relented when the Muslim leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah pushed hard for it. The always-inclusive Gandhi, in trying to insure peace before and after Independence by reassuring and appeasing India’s sizeable Muslim minority, made other concessions that angered certain right-wing orthodox Hindu factions. A member of one of these factions assassinated Gandhi on Jan. 30, 1948 with a pistol shot at close range as he walked with his fellow lovers of God to attend the evening prayer session in Delhi. The Divine name (“Hey Ram”) instantly came to the devout Gandhi’s lips upon his being shot. Gandhi was to have received the Nobel Peace Prize later that year, an award he had been denied several times since being nominated for the first time in 1937. (Decades later, the Nobel Committee publicly declared its regret for the omission, admitting that deeply divided nationalistic opinion was the reason.) With Gandhi dead, the Peace Prize was respectfully not awarded at all in 1948, on the grounds that "there was no suitable living candidate" that year other than the late Mahatma. John Dear, a Jesuit priest, author, and longtime advocate of nonviolence, has succinctly, cogently and eloquently gleaned key aspects of Gandhi's ministry and significance for our time and all times: "Gandhi's primary contribution to spirituality and the world itself is nonviolence.... Gandhi challenges people of faith to recognize the hypocrisy in their lives. He argued that we cannot go to church, synagogue and mosque one day, and the next day sanction war, support executions, foster racism, or pay for nuclear weapons.... For Gandhi, the only authentic spirituality is a spirituality of nonviolence.... [His] influence on Christianity is particularly important. He proclaimed that to be a Christian one has to practice nonviolence. Anything less is not just infidelity but betrayal.... Christians need to take seriously Jesus' last words to the community, 'Put away the sword.'... Second, 'noncooperation with evil is as much a duty as cooperation with the good,' Gandhi said during the Great Trial of 1922.... We need to be publicly active in promoting the common good as well as organizing against the common evil.... Third, Gandhi thought that faith pushes us to promote peace and justice, but he revived the deep wisdom held by every ancient religious tradition that the way to positive, nonviolent social change for peace is through peace and sacrifice. Gandhi insisted that these issues are a matter of life and death, that they are spiritual questions, and that peace and justice require lifelong dedication and the willingness to suffer and die.... Fourth, Gandhi teaches us to accept suffering, even to court suffering, if we want personal transformation, political revolution, and a vision of God. 'Nonviolence ... means the pitting of one's whole soul against the will of the tyrant.'... When asked to sum up the meaning of life in three words or less, Gandhi responded cheerfully, 'That's easy: Renounce and enjoy.' Today it is not popular to talk about self-denial or voluntary suffering, but Gandhi talked about it all the time. The key to his daring achievements lies in his own ongoing suffering, including his poverty, celibacy, arrests, imprisonments, attacks, and assassination.... Fifth, though Gandhi was a lawyer, politician, and revolutionary, he acknowledged that his most powerful weapon was prayer. Through his daily meditation, he came to believe in the presence and nearness of God in day-to-day life. He did not see visions or hear voices, but his prayer led him to a near total reliance on God that gave him the faith ... to undertake his bold public actions for justice and independence.... Sixth, Gandhi held that radical purity of heart bears enormous positive ramifications for the entire world.... He firmly believed that the more we purify our lives, the more our lives will serve God's work to end war, poverty, and injustice. He taught that personal integrity is necessary for an authentic spirituality, for nonviolence. To this end, he suggested regular fasting ... and became an advocate and proponent of fasting as a way to repent of one's personal sins and the sins of those we love.... Seventh, Gandhi practiced a living solidarity with the poor and oppressed. Long before liberation theology, Gandhi gave away his money and personal possessions, renounced his career, moved to a communal farm, made his own clothes, dressed like the poorest Indian peasants, and shared their meager diet of fruits and vegetables. His willingness to go to jail and his defense of the untouchables [the harijan "children of God"] were other ways to share in the poverty of the masses.... Eighth, Gandhi advocated powerlessness as the path to God. Though he mingled with kings and viceroys and was hailed as the father of India, he preferred the company of the poor.... Ninth, Gandhi taught that each of the world's religions has a piece of the truth and deserves our respect.... Tenth, Gandhi held that the spiritual life, as well as all political and social work, requires a fearless pursuit of truth.... Eleventh, Gandhi urged that we let go of results and simply trust in the goodness of the struggle for peace itself. Renunciation of results was a hallmark of the Bhagavad Gita and became of the centerpiece of Gandhi's personal theology.... Twelfth, Gandhi understood these basic principles of truth and nonviolence not just as romantic ideals or pious platitudes, but as actual laws of the universe, with the same palpable hold as the law of gravity. If we pursue truth and nonviolence, our lives will bear the good fruit of truth and nonviolence, Gandhi said." (John Dear [Ed.], Mohandas Gandhi: Essential Writings, Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2002, pp. 39-45)

After the Mahatma's passing, Vinobha Bhave and others continued his legacy of modeling peace, love, nonviolent resistance to injustice, and transforming village life through self-reliance, hard work, and an attitude of self-surrender to Divine Providence. Time Magazine named Gandhi "Man of the Year" in 1930, the runner-up to Albert Einstein as "Person of the Century" at the end of 1999, and named H.H. the Dalai Lama of Tibet, Lech Walesa of Poland, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Cesar Chavez of the USA, Aung San Suu Kyi of Burma/Myanmar, Benigno Aquino, Jr. of the Philippines, and Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela of South Africa as "Children of Gandhi," his spiritual heirs to non-violence. (There are, of course, many other figures one could name as inspired by Gandhi, working and struggling nonviolently on the front lines of various political, economic, and environmental justice issues.) Gandhiji's quasi-religious foundations, the Sabarmati Ashram and Sevagram village, still flourish. His voluminous writings are preserved in a massive publication effort of over 50,000 pages in various languages by the Indian government, The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vols. 1-100, each volume circa 500 pages (New Delhi: Publications Div., Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India, copyright Navajivan Trust [Ahmedabad], 1958-84; also available on a multi-media CD). A more accessible collection would be The Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, 6 vols. (Shriman Navayan, Ed.), Navajivan, 1968, or the single volume Selections from Gandhi (S. Navayan, Ed.), Navajivan, 1957; The Gandhi Reader (Jack Homer, Ed.), Indiana Univ. Press, 1956 (and reprints); or Mohandas Gandhi: Essential Writings (John Dear, Ed.), Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2002. Gandhi's biographers and appreciators and their objective chronicles and/or reminiscences are many, and include Joseph Doke (1909, the earliest assessment), Romain Rolland (1924), C.F. Andrews (1931), H. Muzumdar (1932, 1963), R.R. Diwakar (1949, 1964), Louis Fischer (1950), Vincent Sheehan (1950), D.G. Tendulkar (8 vols., 1951-4), N.K. Bose (1953, 1967), John Haynes Holmes (1954), Pyarelal and Sushila Nayar (10 vols., 1956 on), P.C. Ghosh (1968), Geoffrey Ashe (1968), Robert Payne (1969), Judith Brown (1989), Stanley Wolpert (2001), et al. Of the many documentary and dramatic films on Gandhi, the most complete is the 314-minute "Mahatma," with shorter 2-hour and 1-hour editions also available, directed by Vithalbhai Jhaveri and produced in 1968 by the Gandhi National Memorial Trust, all 3 English-language (and other language) editions available for free viewing at http://streams.gandhiserve.org/mahatma.html. See also the 37-minute documentary film "Gandhi" (Men of Our Time series, 1963, directed and narrated by James Cameron); the multi-award winning, 3-hour cinematic dramatization of his life, "Gandhi" (1982; starring Ben Kingsley, directed by Sir Richard Attenborough); and the 140-minute documentary "A Force More Powerful" (2000) focusing on Gandhi, his principles of ahimsa and satyagraha, and their use by him and others in nonviolent campaigns worldwide (USA, India, S.Africa, Poland & Chile). Other resources: Websites: A very comprehensive collection of Gandhi's voluminous and wide-ranging teachings, organized by topic, can be found at “The Mind of Mahatma Gandhi,” www.mkgandhi.org/momgandhi/momindex.htm, which, in turn, is part of the larger Gandhian Institutes website at www.mkgandhi.org/index.htm Mahatma Gandhi Media and Research Center www.gandhiserve.org/ (Berlin, Germany) M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence, directed by one of the Mahatma's grandsons, Arun Gandhi, was formerly located at 650 East Parkway South, Memphis, TN; it has re-located in Summer-Fall 2007 to the University of Rochester (NY); the longtime website www.gandhiinstitute.org/ no longer seems to be active; look for it or a new domain to come online again soon.

Words of Mahatma (Great Soul) Mohandas K. Gandhi [Given in parenthesis after each selected quote are abbreviations for sources used for these quotes, namely: “A”—An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Boston: Beacon Press, 1957; originally published in 2 vols., 1927/1929); “N”—Non-Violence in Peace & War, vol. 2 (Ahmedabad, India: Navajivan Press, 1949); Roman numerals after certain quotes are from sections of the extensive website, “The Mind of Mahatma Gandhi,” at www.mkgandhi.org/momgandhi/momindex.htm; numbers following the Roman numerals are endnote numbers from those sections (sources can be looked up in Glossary at website). Note that at the end of this long selection of quotes are provided a few lists of principles and guidelines for the conduct of a satyâgrahi, someone who practices satyâgraha, "truth-force."]

Satyâgraha [“holding to Truth,” non-violent “truth-force” or “soul force”] can rid society of all evils, political, economic and moral. (N) For me, truth [Satya] is the sovereign principle, which includes numerous other principles. This truth is not only truthfulness in word, but truthfulness in thought also, and not only the relative truth of our conception, but the Absolute Truth, the Eternal Principle, that is God. There are innumerable definitions of God, because His manifestations are innumerable. They overwhelm me with wonder and awe…. I have not yet found Him, but I am seeking after Him…. Often in my progress I have had faint glimpses of the Absolute Truth, God, and daily the conviction is growing upon me that He alone is real and all else is unreal. (A xiii-xiv) What matters, then, whether one man worships God as Person and another as Force? Both do right according to their lights.... The ideal must always remain the ideal. One need only remember that God is the Force among all the forces. All other forces are material. But God is the vital force or spirit which is all-pervading, all-embracing and, therefore, beyond human ken. (IV 108) To me God is Truth and Love; God is ethics and morality; God is fearlessness. God is the source of Light and Life and yet He is above and beyond all these.... He is a personal God to those who need His personal presence. He is embodied to those who need His touch. He is the purest essence. He simply is to those who have faith.... He is in us and yet above and beyond us… He cannot cease to be because hideous immoralities or inhuman brutalities are committed in His name.... Therefore it is that Hinduism calls it all His sport—lila, or calls it all an illusion—maya. We are not, He alone Is.... Let us dance to the tune of His bansi-flute, and all would be well. (II 38) I know that I can do nothing. God can do everything. O God, make me Thy fit instrument and use as thou wilt! (II 33) I have been a willing slave to this most exacting Master for more than half a century. His voice has been increasingly audible, as years have rolled by. He has never forsaken me even in my darkest hour. He has saved me often against myself and left me not a vestige of independence. The greater the surrender to Him, the greater has been my joy. (II 152) Society must naturally be based on truth and non-violence which, in my opinion, are not possible without a living belief in God, meaning a self-existent, all-knowing living Force. (N 107) God is all in all. We are only zeroes. (N 241) We are drops in that limitless ocean of mercy. (N 311) Not until we have reduced ourselves to nothingness can we conquer the evil in us. God demands nothing less than complete self-surrender as the price for the only real freedom that is worth having. And when a man thus loses himself, he immediately finds himself in the service of all that lives. It becomes his delight and his recreation. He is a new man, never weary of spending himself in the service of God's creation. (IV 116) Let us pray that He may cleanse our hearts of pettinesses, meannesses and deceit and He will surely answer our prayers. (II 50) To see the universal and all-pervading Spirit of Truth face to face, one must be able to love the meanest [lowest] of creation as oneself. And a man who aspires after that cannot afford to keep out of any field of life. That is why my devotion to Truth has drawn me into the field of politics; and I can say without the slightest hesitation, and yet in all humility, that those who say that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means. (A 504) My political friends despair of me... they say that even my politics are derived from religion. And they are right. All ... activities of mine are derived from my religion. ... Every act of a man of religion must be derived from his religion, because religion means being bound to God, that is to say, God rules your every breath. (IV 167) A perfect vision of Truth can only follow a complete realization of Ahimsa [non-violence]. (A 503-4) Whoever believes in ahimsa will engage himself in occupations that involve the least possible violence. (X 21) Violence can only be effectively met by non-violence. … It requires a lot of understanding and strength of mind…. The difficulty one experiences in meeting himsa [violence] with ahimsa arises from weakness of mind. (N 247) Where there is ahimsa, there is infinite patience, inner calm, discrimination [between the Truth and falsehood], self-sacrifice and true knowledge. (N 282) I have learnt through bitter experience the one supreme lesson to conserve my anger, and as heat conserved is transmuted into energy, even so our anger controlled can be transmuted into a power which can move the world. (I 78) It is not that I do not get angry. I do not give vent to anger. I cultivate the quality of patience as angerlessness, and, generally speaking, I succeed.… It is a habit that everyone must cultivate and must succeed in forming by constant practice. (I 80) I want to identify myself with everything that lives. (I 24) Identification with everything that lives is impossible without self-purification; without self-purification the observance of the law of Ahimsa must remain an empty dream. God can never be realized by one who is not pure of heart. Self-purification means purification in all walks of life. And purification being highly infectious, purification of oneself necessarily leads to purification of one’s surroundings…. To attain to perfect purity one has to become absolutely passion-free in thought, speech and action; to rise above the opposing currents of love and hatred, attachment and repulsion. I know that I have not in me as yet that purity, in spite of constant ceaseless striving for it. That is why the world’s praise fails to move me…. I know that I have still before me a difficult path to traverse. I must reduce myself to zero. So long as a man does not of his own free will put himself last among his fellow creatures, there is no salvation for him. Ahimsa is the farthest limit of humility. (A 504-5) Prayer from the heart can achieve what nothing else can in the world. (N 20) Prayer is an impossibility without a living faith in the presence of God within. (IV 97) Supplication, worship, prayer are no superstition; they are acts more real than the acts of eating, drinking, sitting or walking. It is no exaggeration to say that they alone are real, all else is unreal…. Such worship or prayer … is no lip-homage. It springs from the heart. We achieve that purity of heart when it is ‘emptied of all but love’… (A 72) As I know that God is found more often in the lowliest of His creatures than in the high and mighty, I am struggling to reach the status of these. I cannot do so without their service. Hence my passion for the service of the suppressed classes. And as I cannot render this service without entering politics, I find myself in them. Thus I am no master. I am but a struggling, erring, humble servant of India and therethrough of humanity. (I 56) Self-sacrifice of one innocent man is a million times more potent than the sacrifice of a million men who die in the act of killing others. The willing sacrifice of the innocent is the most powerful retort to insolent tyranny that has yet been conceived by God or man. (VI 49) It is time white men learnt to treat every human being as their equal. It has repeatedly been proved that given equal opportunity a man, be he of any color or country, is fully equal to any other. Do they forget that the greatest of the teachers of mankind [including Jesus] were all Asiatics and did not possess a white face? (N 17) My experience has shown me that we win justice quickest by rendering justice to the other party. (A 182) Man and his deed are two distinct things…. The doer of the deed, whether good or wicked, always deserves respect or pity as the case may be. “Hate the sin and not the sinner” is a precept which, though easy enough to understand, is rarely practised, and that is why the poison of hatred spreads in the world. This ahimsa is the basis of the search for truth. … It is quite proper to resist and attack a system [an unjust one], but to resist and attack its author is tantamount to resisting and attacking oneself. For we are … children of one and the same Creator, and as such the divine powers within us are infinite. To slight a single human being is to slight those divine powers, and thus to harm not only that being but with him the whole world. (A 276) It is easy enough to be friendly to one’s friends. But to befriend the one who regards himself as your enemy is the quintessence of true religion. The other is mere business. (N 241-2) If we accept that ideal [satyagraha/truth-force and ahimsa/non-violence] we would not regard anybody as our enemy; we must shed all enmity and ill-will. That ideal is not meant for the select few—the saint or the seer only; it is meant for all. (N 33-4) I have met human monsters from my early youth. I have found that even they are not beyond redemption, if we know how to touch the right chord in their soul. (N 186) The greatest enmity requires an equal measure of ahimsa for its abatement. (N 327) When the mind is completely filled with His spirit, one cannot harbor ill-will or hatred towards anyone and, reciprocally, the enemy will shed his enmity and become a friend. It is not my claim that I have succeeded in converting enemies into friends, but in numerous cases it has been my experience that, when the mind is filled with His peace, all hatred ceases. An unbroken succession of world teachers since the beginning of time have borne testimony to the same. I claim no merit for it. It is entirely due to God's grace. (IV 119) The virtues of mercy, non-violence, love and truth in any man can be truly tested only when they are pitted against ruthlessness, violence, hate and untruth. (N 82) We must look for danger from within, not fear the danger from without. The first corrodes the soul, the second polishes it. (N 101-102) No outside power can really degrade a man. He only can degrade himself. (N 345) Fearlessness is the first requisite of spirituality. Cowards can never be moral. (III 1) Where there is fear there is no religion. (III 2) Perfect fearlessness can be attained only by him who has realized the Supreme, as it implies the height of freedom from delusions. (III 5) Fearlessness connotes freedom from all external fear--fear of disease, bodily injury or death, of dispossession, of losing one's nearest and dearest, of losing reputation or giving offence, and so on. (III 4) As for the internal foes, we must ever walk in their fear. We are rightly afraid of Animal Passion, Anger and the like. External fears cease of their own accord when once we have conquered these traitors within the camp. All fears revolve round the body as the center, and would, therefore, disappear as soon as one got rid of the attachment for the body. … All these [body, wealth, family, etc.] are not ours but God's. Nothing whatever in this world is ours. Even we ourselves are His. Why then should we entertain any fears? The Upanishad, therefore, directs us 'to give up attachment for things while we enjoy them'. That is to say, we must be interested in them not as proprietors but only as trustees.…When we thus cease to be masters and reduce ourselves to the rank of servants humbler than the very dust under our feet, all fears will roll away like mists; we shall attain ineffable peace and see Satyanarayan (the God of Truth) face to face. (III 5) A Satygrahi [civil resister practicing non-violent satyagraha or Truth-force] must always be ready to die with a smile on his face without retaliation and without rancor in his heart. (N 21) Far more potent than the strength of the sword is the strength of Satyagraha. (N 35) To lay down one’s life, even alone, for what one considers to be right, is the very core of Satyagraha. More, no man can do. If a man is armed with a sword he might lop off a few heads but ultimately he must surrender to superior force or else die fighting. The sword of the Satyagrahi is love and the unshakable firmness that comes from it. He will regard as brothers the hundreds of thugs who confront him and instead of trying to kill them he will choose to die at their hands and thereby live. (N 58) The golden rule of life: to exaggerate one’s own faults and make little those of others. That [is] the only way to self-purification. (N 369) Satyagraha is never vindictive. It believes not in destruction but in conversion. Its failures are due to weaknesses of the Satyagrahi.... (N 143) God rules even where Satan seems to hold sway, because the latter exists only on His sufferance. Some people say that Satyagraha is of no avail against a person who has no moral sense. I [take] issue with that. The stoniest heart must melt if we are true and have enough patience. (N 104) The root of Satyagraha is in prayer. A Satyagrahi relies upon God for protection against the tyranny of brute force. (N 61) Prayer is the first and last lesson in learning the noble and brave art of sacrificing self in the various walks of life culminating in the defence of one’s nation’s liberty and honor. Undoubtedly prayer requires a living faith in God. Successful Satyagraha is inconceivable without that faith. (N 75-6) God is the only companion and doer. Without faith in Him these peace brigades will be lifeless. By whatever name one calls God, one must realize that one can only work through His strength. Such a man will never take another’s life. He will allow himself, if need be, to be killed and thereby live through his victory over death. The mind of the man in whose life the realization of this law has become a living reality will not be bewildered in a crisis. He will instinctively know the right way to act. … He should recite Ramanama [i.e., one of the Names of God] ceaselessly in his heart… (N 83-4) Striving has to be in a spirit of detachment. (N 332) Mankind is at the crossroads. It has to make its choice between the law of the jungle and the law of humanity. (N 56) Mankind has to get out of violence only through non-violence. Hatred can be overcome only by love. (N 93) The military is the very embodiment of madness. (N 62) War is a respectable term for goondaism [hooliganism] on a mass or national scale. (N 143) We are discussing a final substitute for armed conflict called war, in naked terms mass murder. (N 89) The gospel of ahimsa [nonviolence] can be spread only through believers dying for the cause.... He who when being killed bears no anger against his murderer and even asks God to forgive him is truly non-violent. (N 91-2, 82) The training for Satyagraha is meant for all, irrespective of age or sex. The more important part of the training here is mental, not physical. … Satyagraha is always superior to armed resistance. This can only be effectively proved by demonstration, not by argument. It is the weapon that adorns the strong. It can never adorn the weak. By weak is meant the weak in mind and spirit, not in body. … It can never be used to defend a wrong cause. (N 59) Satyagraha is a process of educating public opinion, such that it covers all the elements of society and in the end makes itself irresistible. … The conditions necessary for the success of Satyagraha are: 1) The Satyagrahi should not have any hatred in his heart against the opponent. 2) The issue must be true and substantial. 3) The Satyagrahi must be prepared to suffer until the end. (N 60) You are no Satyagrahis if you remain silent or passive spectators while your enemy is being done to death. You must protect him even at the cost of your life. (N 62) A Satygrahi should fast [unto death in civil disobedience] only as a last resort when all other avenues of redress have been explored and have failed. … It is wrong to fast for selfish ends, e.g., for increase in one’s own salary. Under certain circumstances it is permissible to fast for an increase in wages on behalf of one’s group. (N 48) Success and failure are not in your hands, but in God’s hands alone. (N 37) Let us ... resign ourselves to Him. His will be done. (N 191) [Gandhi reflected in 1946:] The lesson of the last 25 years of training in non-violence has gone home to the masses. They have realized that in non-violence they have a weapon that enables a child, a woman or even a decrepit old man to resist the mightiest government successfully. If your spirit is strong, mere lack of physical strength ceases to be a handicap. (N 41) [On the possibility of non-violence triumphing over violence:] History provides us with a whole series of miracles of masses of people being converted to a particular viewpoint in the twinkling of an eye. (N 158) I remain an optimist, not that there is any evidence that I can give that right is going to prosper, but because of my unflinching faith that right must prosper in the end….. Our inspiration can come only from our faith that right must ultimately prevail. (I 6) If we could erase the 'I's’ and the 'Mine's' from religion, politics, economics, etc., we shall soon be free and bring heaven upon earth.(I 15) Today, in the West, people talk of Christ, but it is really the Anti-Christ that rules their lives. Similarly, there are people who talk of Islam, but really follow the way of Satan. It is a deplorable state of affairs. …If people follow the way of God, there will not be all this corruption and profiteering that we see in the world. The rich are becoming richer and the poor poorer. Hunger, nakedness and death stare one in the face. These are not the marks of the Kingdom of God, but that of Satan, Ravana or Anti-Christ. We cannot expect to bring the reign of God on earth by merely repeating His name with the lips. Our conduct must conform to His ways instead of Satan’s. (IV 54) The economics that permit one country to prey upon another are immoral. [And] it is sinful to buy and use articles made by sweated labor. (X 15) According to me the economic constitution of India and, for the matter of that, the world should be such that no one under should suffer from want of food and clothing.…And this ideal can universally realized only if the means of production of the elementary necessaries of life remain in the control of the masses. These should be freely available to all as God’s air and water are or ought to be; they should not be made vehicle of traffic for the exploitation of others. This monopolization by any country, nation or group of persons would be unjust. The neglect of this simple principle is the cause of destitution that we witness today not only in this unhappy land but other parts of the world too. (X 18) Today there is gross economic inequality. The basis of socialism is economic equality. There can be no Ramarajya [Divine rule or Kingdom of God] in the present state of iniquitous inequalities in which a few [people] roll in riches and the masses do not get even enough to eat. (X 28) A violent and bloody revolution is a certainty one day unless there is a voluntary abdication of riches and the power that riches give and sharing them for the common good. (X 1) People with talents will have more, and they will utilize their talents for this purpose. If they utilize their talents kindly, they will be performing the work of the State. Such people exist as trustees.... I would allow a man of intellect to earn more, I would not cramp his talent. But the bulk of his greater earnings must be used for the good of the State, just as the income of all earning sons of the father go to the common family fund. [...] Economic equality of my conception does not mean that everyone will literally have the same amount. It simply means that everybody should have enough for his or her needs.…The real meaning of economic equality is "To each according to his need." That is the definition of Marx. If a single man demands as much as a man with wife and four children, that will be a violation of economic equality. Let no one try to justify the glaring difference between the classes and the masses, the prince and the pauper, by saying that the former need more. That will be idle sophistry and a travesty of my argument. The contrast between the rich and the poor today is a painful sight. The poor villagers are exploited by…their own countrymen—the city-dwellers. They produce the food and go hungry. They produce milk and their children have to go without it. It is disgraceful. Everyone must have a balanced diet, a decent house to live in, and facilities for the education of one's children and adequate medical relief…. Under my plan the State will be there to carry out the will of the people, not to dictate them or force them to do its will. I shall bring about economic equality through non-violence, by converting the people to my point of view by harnessing the forces of love as against hatred. I will not wait till I have converted the whole society to my view, but will straightaway make a beginning with myself. It goes without saying that I cannot hope to bring about economic equality of my conception if I am the owner of fifty motor cars or even of ten bighas of land. For that I have to reduce myself to the level of he poorest of the poor. (X 23, 25) Under State-regulated trusteeship, an individual will not be free to hold or use his wealth for selfish satisfaction or in disregard of the interests of society. Just as it is proposed to fix a decent minimum living wage, even so a limit should be fixed for the maximum income that would be allowed to any person in society. The difference between such minimum and maximum incomes should be reasonable and equitable and variable from time to time so much so that the tendency would be towards obliteration of the difference. Under the Gandhian economic order the character of production will be determined by social necessity and not by personal whim or greed. (X 14) I adhere to my doctrine of trusteeship in spite of the ridicule that has been poured upon it. It is true that it is difficult to reach. So is non-violence. But we made up our minds in 1920 to negotiate that steep ascent. We have found it worth the effort. (X 2) My theory of ‘trusteeship’ is no make-shift, certainly no camouflage. I am confident that it will survive all other theories. It has the sanction of philosophy and religion behind it. That possessors of wealth have not acted up to the theory does not prove its falsity; it proves the weakness of the wealthy. No other theory is compatible with non-violence. (X 7) Supposing I have come by a fair amount of wealth—either by way of legacy, or by means of trade and industry—I must know that all that wealth does not belong to me; what belongs to me is the right to an honourable livelihood, no better than that enjoyed by millions of others. The rest of my wealth belongs to the community and must be used for the welfare of the community. (X 6) Should the wealthy be dispossessed of their possessions? To do this we would naturally have to resort to violence. This violent action cannot benefit society. Society will be the poorer, for it will lose the gifts of a man who knows how to accumulate wealth. Therefore the non-violent way is evidently superior. The rich man will be left in possession of his wealth, of which he will use what he reasonably requires for his personal needs and will act as a trustee for the remainder to be used for the society.…As soon as a man looks upon himself as a servant of society, earns for its sake, spends for its benefit, then purity enters into his earnings and there is ahimsa in his venture. Moreover, if men's minds turn towards this way of life, there will come about a peaceful revolution in society and that without any bitterness.… It may be asked whether history at any time records such a change in human nature. Such changes have certainly taken place in individuals. One may not perhaps be able to point to them in a whole society. But this only means that up till now there has never been an experiment on a large scale on non-violence…. If, however, in spite of the utmost effort, the rich do not become guardians of the poor in the true sense of the term and the latter are more and more crushed and die of hunger, what is to be done? In trying to find out the solution of this riddle, I have lighted on non-violent non-co-operation and civil disobedience as the right and infallible means. The rich cannot accumulate wealth without the co-operation of the poor in society.…If this knowledge [of ahimsa] were to penetrated to and spread amongst the poor, they would become strong and would learn how to free themselves by means of non-violence from the crushing inequalities which have brought them to the verge of starvation. (X 32) I want to deal with one great evil that is afflicting society today. The capitalist and the zamindar [landowner] talk of their rights, the laborer on the other hand of his [rights], the prince [maharaja] of his divine right to rule, the ryot [agricultural tenant] of his [right] to resist it. If all simply insist on rights and no duties, there will be utter confusion and chaos. If instead of insisting on rights everyone does his duty, there will immediately be the rule of order established among mankind.… Rights that do not flow directly from duty well-performed are not worth having.… If you apply this simple and universal rule to employers and laborers, landlords and tenants, the princes and their subjects, or the Hindus and the Muslims, you will find that the happiest relations can be established in all walks of life … (N 261)

I am a servant of Mussalmans [Muslims], Christians, Parsis and Jews as I am of Hindus. (I 67) Let me explain what I mean by religion. It is not the Hindu religion which I certainly prize above all other religions, but the religion which transcends Hinduism, which changes one's very nature, which binds one indissolubly to the truth within and which ever purifies. It is the permanent element in human nature which counts no cost too great in order to find full expression and which leaves the soul utterly restless until it has found itself, known its Maker and appreciated the true correspondence between the Maker and itself. (IV 8) By religion, I do not mean formal religion, or customary religion, but that religion which underlies all religions, which brings us face to face with our Maker. (IV 9) I believe that all the great religions of the world are true more or less. I say 'more or less' because I believe that everything that the human hand touches, but reason of the very fact that human beings are imperfect, becomes imperfect. Perfection is the exclusive attribute of God and it is indescribable, untranslatable. I do believe that it is possible for every human being to become perfect even as God is perfect. It is necessary for us all to aspire after perfection, but when that blessed state is attained, it becomes indescribable, undefinable. And I therefore admit, in all humility, that even the Vedas, the Koran and the Bible are imperfect word of God… (IV 25) A curriculum of religious instruction must include a study of the tenets of faiths other than one's own. For this purpose the students should be trained to cultivate the habit of understanding and appreciating the doctrines of various great religions of the world in a spirit of reverence and broad-minded tolerance. (I 40) The chief value of Hinduism lies in holding the actual belief that all life (not only human beings, but all sentient beings) is one, i.e., all life coming from the One universal source, call it Allah, God or Parameshwara. (IV 127) There are two aspects of Hinduism. There is on one hand the historical Hinduism with its untouchability, superstitious worship of stocks and stones, animal sacrifice and so on. On the other, we have the Hinduism of the [Bhagavad] Gita, the Upanishads and Patanjali’s Yogasutras which is the acme of ahimsa and oneness of all creation, pure worship of one immanent, formless, imperishable God. (N 174-5) I cannot ascribe exclusive divinity to Jesus. He is as divine as Krishna or Rama or Muhammad or Zoroaster. Similarly, I do not regard every word of the Bible as the inspired word of God, even as I do not regard every word of the Vedas or the Koran as inspired. The sum total of each of these books is certainly inspired, but I miss that inspiration in many of the things taken individually. (IV 143) Let no one say that he is a follower of Gandhi. It is enough that I should be my own follower. I know what an inadequate follower I am of myself, for I cannot live up to the convictions I stand for. You are no followers but fellow-students, fellow-pilgrims, fellow-seekers, fellow-workers. (I 129) The highest honour that my friends can do me is to enforce in their own lives the programme that I stand for or to resist me to their utmost if they do not believe in it. (I 52) I have not the shadow of a doubt that any man or woman can achieve what I have, if he or she would make the same effort and cultivate the same hope and faith. (I 59) I believe it to be possible for every human being to attain to that blessed and indescribable, sinless state in which he feels within himself the presence of God to the exclusion of everything else. (II 53) I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and Non-violence are as old as the hills. All I have done is to try experiments in both on as vast a scale as I could do. In doing so I have sometimes erred and learnt by my errors. Life and its problems have thus become to me so many experiments in the practice of truth and non-violence. (I 124) I have only three enemies. My favorite enemy, the one most easily influenced for the better, is the British Empire. My second enemy, the Indian people, are far more difficult. But my most formidable opponent is a man named Mohandas K. Gandhi. With him I seem to have very, very little influence. I am not afraid to die in my mission, if that is to be my fate. (I 77) Do not seek to protect me. The Most High is always there to protect us all. You may be sure that when my time is up, no one, not even the most renowned in the world, can stand between Him and me. (I 70) Even if I am killed, I will not give up repeating the names of Rama and Rahim, which mean to me the same God. With these names on my lips, I will die cheerfully. (IV 90) [And, in fact, upon his assassination, he died with the sweet exclamation of love, Hey Ram, “Oh, Lord God.”]

Principles & Rules for Satyagrahis Gandhi envisioned satyagraha as not only a method for struggling against unjust politics and policies, but as a universal solvent for injustice and harmfulness. He saw it applying equally to large-scale political situations and to one-on-one interpersonal conflicts. Satyagraha, Gandhi insisted, could and should be taught to everyone. He founded the Sabarmati Ashram and later Sevagram to teach satyagraha. He urged satyagrahis to follow certain principles and rules. Principles Rules 1. one must have a living faith in God Rules for Satyagraha Campaigns 1. you must harbour no anger =================== Friend Steve Beckow has organized all of the above principles and rules into the following schema: An Adaptation of Mahatma Gandhi’s Principles of Satyagraha Attitude Towards First Principles · Adhere to the truth, which includes honesty, but goes beyond this to mean living fully in accord with and in devotion to that which is true. Attitude Towards Desires and Possessions · Adhere to chastity (brahmacharya), including sexual chastity, but also including the subordination of other sensual desires to the primary devotion to truth. Attitude Towards Suffering · Be willing to undergo suffering. Attitude Towards Opponents · Harbour no anger. Attitude Towards Laws and Confinement · Appreciate the other laws of the State and obey them voluntarily. Attitude Towards Civil Disobedience · Joyfully obey the orders of the leaders of the civil disobedience action.

|