|

Notes on Judaism© Copyright 1991/2006 by Timothy Conway, Ph.D.(The following is an older essay on Judaism, with some updated elements, that I've been giving as a handout to students in comparative religion classes. I have a very full chapter in an upcoming book manuscript, Our Religions' Future, namely, "Trends, Revivals, and Challenges in Judaism," which contains a lot more historical material on Judaism and discussion of modern-era religious and mystical trends, demographic issues, renewed forms of anti-Semitism, the Jewish Renewal movement, and so forth.)

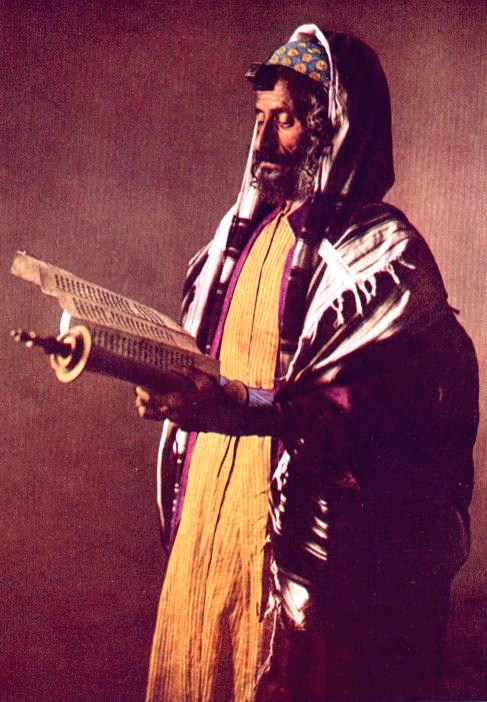

The crux of Judaism is the belief that the Divine Lord, Adonai, whose secret, unutterable Name is YHWH (Yahweh/Jaweh), I Am That Am, is not just some remote, aloof, impersonal principle. No, the Lord, while remaining fully transcendent, is interested in human affairs, often acting to affect the course of history. Specifically, the Lord rewards the good and, if necessary, punishes the evil, so as to bring all beings to "Love the Lord thy God with thy whole soul, mind, heart, and strength" (Deuteronomy, 6:5) and to "Love thy neighbor as thyself." In this way, G-d (observant Jews omit the vowel to hint at G-d's ultimately mysterious Nature) is leading people toward the realization of lasting peace, joy, and social harmony. The numerous ruthless, violent harassments and pogroms directed against the Jews over the course of their history—and the Jews have definitely been persecuted more than any other group of people on the planet—are not due to the failure of G-d nor any inherent sinfulness on the part of the Jews, but are seen by Jews as being a sign of their special commitment to upholding an exclusive covenant with the one G-d. The basic sacred scriptures for the world’s 14.3 million Jews are 1) the Torah, the Law or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Tanakh/Hebrew Bible (what Christians misleadingly refer to as the "Old Testament"), followed by 2) the works of the Nevi'im/Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the ten minor prophets), and then that body of literature known as 3) the Kethuvim/Writings or Hagiographa—namely, Psalms, Job, Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah and Chronicles. This entire Canon would not be formalized until the early 2nd century CE (Common Era, i.e., "after Christ"). Of these three collections, it is the works of prophets Amos, Hosea, Micah, and Isaiah that are probably the earliest writings, dating from about the 8th century BCE. The Torah, or Divine "Teachings," the most sacred of Jewish scriptures, was not written by Moses, as often maintained, but rather is an extremely heterogeneous (mixed), composite text which was compiled by scribes and scholars after the Babylonian exile of the Jews in 586 BCE and not finalized until the 4th century BCE. The Torah is filled with stories handed down by the Jews from much more ancient times. Some of these stories, like the account of Creation, the Garden of Eden, and Noah and the Flood, actually come down from more ancient Sumerian/Mesopotamian sources, and are somewhat distorted versions of the Sumerian stories. Interestingly, recent speculation holds that those passages of the Torah which refer to G-d as Jaweh / Yahweh (and thus these passages are called the "J" strata of the Torah) were actually written by a sophisticated Israelite woman. (Jack Miles has suggested it was the Hittite or Cananite lady Bathsheba, the young wife of King David.) Other sections of the Torah are known as "E" (these refer to G-d as Elohim); "P" (the Priestly redaction, containing items especially relevant to the Jewish priesthood); and "D" (material from Deuteronomy). Ancient Hebrews first appear on the historical scene as a nomadic tribe of people of the northern Arabian peninsula, at the fringe of the desert, possessing a culture similar to many others of the neolithic period (Stone Age). Like other neolithic people, they believed that various deities (Elohim) and extra life force (mana) pervaded certain extraordinary, sacred natural objects, such as strange rock-formations, mountains, the sky, trees, etc. Around 2000 BCE the Hebrews migrated north into Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). According to the Bible, 100 to 300 years later they were led in a meandering, southwestly direction into Canaan (today known as Palestine, the northern part of the Sinai peninsula) by the first patriarch of the Israelites, Abraham of Ur and Haran (towns in Mesopotamia). The Hebrews would continue to move southwest, occupying the land of Goshen on the east side of the Nile Delta. Abraham is said to have founded the monotheistic religion of the Jews, making a covenant of obedience with G-d; it seems that for him the name of the Lord was El-Shaddai, usually translated "Divinity of the Mountains," but some scholars have observed that this also means "the Breasted One," suggestive of a maternal, nurturing Protector. Canaanite religion at the time was polytheistic, entailing some 70 gods, headed by the high god El, his wife Asherah, and their son Baal. El was a generic Canaanite term for divinity, and it figures prominently in the Hebrew Bible as a name for G-d, along with its plural form, Elohim. Two other patriarchs followed Abraham—Isaac and Jacob/Israel, pastoral nomads. One of Jacob's 12 sons, Joseph, became an advisor to an Egyptian ruler, and thereafter Jacob and his other sons moved to the Goshen area of Egypt, ushering in a period during which the Jews lived in Egypt as farmers and laborers. According to tradition, the real father of Jewish religion is Moses, the adopted Jewish son of an Egyptian princess, who lived about the 12th century BCE. He is said to have been exiled from Egypt due to his sympathy for his Jewish people, who were being subjected to forced labor and their sons killed by Pharaoh, who feared the burgeoning population of Jews. Settling in Midian, to the east of the upper region of the Red Sea, Moses married and became a shepherd. One day, while tending his father-in-law's flock, he was drawn to Mt. Horeb, and there underwent some kind of transformative encounter with a numinous phenomenon—an angel of the Lord appearing to him in a flame of fire permeating a bush. Moses then received a command from G-d to lead the Israelites out of Egypt. It was during this encounter that G-d revealed himself as I AM THAT AM, the supreme Name of G-d, abbreviated by Jews as the tetragrammaton, YHWH. After partially overcoming his sense of unworthiness, Moses, with the help of his brother, Aaron, confronted Pharaoh with the Divine command. Eventually, after the power of Yahweh had defeated the power of the Egyptian magicians, Moses and the Jewish people made the great Exodus out of Egypt. While they wandered in the desert for some years, Moses received the great divine Teachings (Torah) on Mt. Sinai, which include the Ten Commandments, the basis for Jewish spirituality and ethics. The Ten Commandments were evidently inscribed on two stone tablets, which in turn were placed in a sacred ark (the Ark of the Covenant) housed in a portable tabernacle. Their new covenant with G-d helped the Jews to endure the various tribulations during their wanderings, and, through Moses' inspired leadership, they witnessed the saving power of G-d. After the death of Moses, the Jews under Joshua were able to capture the ancient city of Jericho, and settle in Canaan. The monotheistic religion of YHWH grew stronger over the generations with persistent efforts by the Jewish leaders, staunchly supported by the Levites, who presided over the ark and the sanctuary. After a period of being ruled and advised by a number of judges (including the female judge, Deborah), the last and most famous of whom was Samuel, the Jews elected a king, Saul, to unify and lead them. This was a mixed blessing, in that monarchical rule violated the spirit of egalitarianism (imperfect though it be) which had characterized the Jewish people until that time. Saul died in battle, and was followed by the illustrious shepherd, poet and "giant-slayer," David. During the reign of King David's son, Solomon, the great Temple at Jerusalem was built to house the Ark of the Covenant. However, King Solomon's marital ties with numerous non-Jewish women led him to build altars and temples to other gods, and it is said that, due to his forgetting the pure monotheism of the Patriarchs, Israel incurred G-d's wrath. After his death the kingdom split into two rival factions, Judah in the south, with Jerusalem its capital, and Israel in the north of the Palestine area. The Bible relates that Israel became so corrupt, turning to magical practices and worship of Baal and ignoring the inspired plea of prophets Elijah, Amos, Hosea and Isaiah to return to sincere, pious, monotheistic worship of YHWH, that G-d allowed the Assyrians to destroy it in 722 BCE. The dispersed people would henceforth be known as the "Ten Lost Tribes of Israel." Judah continued along for a few more centuries, but it also fell away from exclusive worship of YHWH and eventually also was vanquished, by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, in 586. The Temple was destroyed, the treasures taken, and the elite Jewish class taken off in exile to Babylon, the working people remaining behind to eke out an existence. After fifty years the Jews were fortuitously allowed by Persian King Cyrus to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple (consecrated in 516 BCE). Temple rites began be developed and the Torah was compiled by an hereditary priesthood tracing its ancestry to back to Aaron, Moses' brother. Jewish religion had been inspired during this period by prophets such as Jeremiah and Ezekiel, but it was prophet Ezra whose ministry brought the Torah completely into the minds and hearts of the people, precluding an exclusively priest-dominated form of religion. Yet over the next several centuries Jewish religion would be greatly influenced by the rationalism and humanism of the Greeks and by Zoroastrian ideas prominent in Persia (the latter included the concept of Satan, an angelic hierarchy, bodily resurrection, and an apocalyptic final Day of Judgement). At one point during this period King Antiochus of Syria tried to completely Hellenize Judea and abolish the Torah, but a revolt led by the Hasmon family, the Maccabean rebellion (167-142 BCE), helped Judea to remain independent and preserve the distinctive Jewish belief. Four main groups of Jews emerged: Sadducees, conservative "letter-of-the-law" priests and wealthy business-people; Pharisees, devout yet more liberal scribes, rabbis and citizens of all social classes (the two greatest religious teachers of the age, Hillel and Shammai, were Pharisees); Zealots, fervently awaiting a Messiah, intolerant of foreign (Roman) rule; and Essenes, a strict, ascetic, mystic monastic group, with marked Zoroastrian and Orphic influence in their rather Messianic ideas. In 142 BCE the Essenes withdrew from society (they considered the Hasmonean priesthood to be invalid and corrupt) and established themselves as a community in the wilds of Qumran near the Dead Sea, at one point led by an illustrious "Teacher of Righteousness" (the Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in 1947 and finally released to scholars in 1992, are fragments of many writings made by this group). (Note: at least one other mystical, ascetical group of Jews flourished in the ancient world, the Therapeutae, outside Alexandria, Egypt.) The Sadducees and Pharisees began a civil war over their significant differences; Roman general Pompey was called in to settle the dispute, but instead took over the country. A Zealot-inspired Jewish rebellion broke out in the year 66 of the Common Era, but in 70 CE the Jews were defeated and slaughtered. Jerusalem (along with all other Judean towns) and the Temple were destroyed, and Jewish religion proscribed. At this point, Judaism almost completely perished. Of the various groups of organized Jews who survived in Diaspora (Gola), two were most important: 1) the rabbis, inheritors of the Pharisee tradition; they studied, taught and preached in the bet ha-Midrash ("house of study") and democratically worshipped (sans priesthood) in synagogues, "meeting places" (in lieu of the Temple)—and carried on liturgical prayer through reading of the Torah; and 2) the relatively new, heretical Jewish sect of the Nazarenes, or Christians; they followed the deceased, charismatic, eschatalogical teacher or rabbi Yeshua ("Jesus"), considering him to have been the long-awaited Messiah/Mashiah (annointed one) who would come again in the near future to establish the rule of G-d upon the earth. As time progressed, the Christians became more and more Hellenized, picking up many pagan elements from Greek and Roman thought, including elements from the mystery schools of the Mediterranean (e.g., the cult of Mithras), until Christianity had seriously diverged from Judaism. Jewish theology and spiritual practice would remain significantly different from Christianity in the following ways: Jews hold that G-d is One ("Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our G-d, the Lord is One!"—Shema Israel, Adonai Elohenu, Adonai Ehod!), G-d is not a Trinity; G-d is formless and will never assume form (as in the person of Jesus); no human will ever be divine or perfect (even the patriarchs and prophets were human and fallible); everyone has direct access to G-d, without need for any intermediaries between humanity and the divine; the soul is not burdened by any "original sin" in need of Jesus' atonement via his death; obedience to the commands of Torah are sufficient for salvation, not belief in the saving power of Jesus; there is no need for sacraments to bring down G-d's grace to the people; finally, Jews maintain that the New Testament is not divinely revealed, but a human work, and laced with anti-Jewish sentiment (due to Christians' aligning with Rome). The Jewish rabbis of Palestine and Babylonia, whose Pharisaic Judaism became normative and soon absorbed all other surviving Jewish groups, were compelled to gather together all the writings important to their identity as a people and religion. The Tanakh or Bible was compiled into virtually finished form (with its three general sections—Torah, Nevi'im, and Kethuvim) in the year 90 of the Common Era, with the idea that the time of divine revelation was over. Around 135 CE a few other writings, such as Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes, which included more "liberal" ideas such as the resurrection of the dead, were also accepted into the canon. From this time onward the rabbis adopted two basics tasks, collectively known as Midrash: biblical exegesis (applying biblical teachings to contemporary lives) and mystical interpretation of the bible, especially the Torah. By the end of the 6th century CE the rabbis' exegetical and mystical writings, including the rabbinical writings of the old Pharisaism in the centuries before the Common Era, had been brought together into the Talmud, comprised of two sections, the Mishnah, or earlier portion, and the Gemara, or later, larger portion (an elaborate commentary on the Mishnah). The Talmud (which exists in both Palestinian and Babylonian forms) is a vast encyclopedia of rabbinic learning, piety, wisdom and legal ingenuity clarifying the biblical writings. The Talmud sets into place the main festivals of Judaism, including the Pesach or Passover feast, celebrating the exodus by Moses and the people (a Seder feast was substituted by the rabbis for the sacrifice of the paschal lamb), Yom Kippur or Feast-Day of the Atonement (the last of the Days of Awe which commence with the New Year; a time of fasting and uninterrupted prayer for atonement), and less serious, even more joyous festivals such as Hanukkha or Feast of Lights (in December), celebrating the re-dedication of the Temple by Judas Maccabaeus in 165 BCE, and Purim or Feast of Lots (in late February), celebrating Queen Esther's saving the Jewish people from persecution in 480 BCE. These festivals underscore the importance of the notion of community and a Divinely-guided history as crucial elements in Jewish religion. Observance of the Talmudic code enabled the Jewish people to retain their identity over the centuries down to this day, even while they were assimilating first Greek, then Muslim, then scientific and secular-humanistic ideas. (Today there are many Jews who have retained their fundamental Jewishness while learning from and even participating in forms of Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, etc.) We should at this point mention some of the eminent Jewish thinkers from the period just before the Diaspora down through the centuries. Philo (20 BCE to 50 CE), actually blended together Jewish and Greek thought in a way which constituted a signficant departure from traditional Jewish thinking, undoubtedly the reason why he was almost completely forgotten by later Jewish tradition (his memory was preserved by Christian Church Fathers). A true mystic, Platonist in orientation, he emphasized a life of contemplation of the transcendent G-d, who, by the power of His Grace as the principle of the Logos/Word, makes himself known to the highest part of the intellect in human beings. Philo's allegorical interpretation of the Torah (seeing Abraham's journey, Moses' exodus, etc., as symbolic of the soul moving toward G-d) and his negative theology would be highly influential not only for Christian via negativa mystical theology but also for later Jewish Kabbalistic mystical thought. Esoteric forms of Jewish mystical thinking and meditative practice had been developing all along, such as Merkava/Merkabah "Heavenly Throne" mysticism, which dates from the "First Hasidim" (Holy Ones) in the early centuries of the Common Era, flourishing in Babylonia and the Byzantine empire up to the 7th-8th centuries, thereafter moving, via Italy, up to Germany. This mystical view, elucidated in closed circles by certain rabbis, emphasized the ascension of the soul into a numinous vision of divine glory, symbolized by the divine throne (merkabah). Related to this was the Hekhalot mysticism of visualizing various sages or oneself being carried up to the "heavenly palace" on a chariot like Elijah. It is said that the early leading mystics and teachers of these esoteric forms of inner spirituality included the following great Talmudic Rabbis: Hillel (late 1st cent. BCE to early 1st cent. CE), who came from Babylonia to Palestine c40 CE, and, as leader of the community (nasi), preached universal brotherhood. In the more than 300 controversies over orthopraxy between his school and that of the rather rigid Shammai, Hillel took more lenient viewpoints, in solidarity with the generally underprivileged common man (Shammai was more identified with the priests and affluent). Hillel's school was recognized as authoritative, and almost all of its decisions were accepted. Hillel, a "paragon of many virtues—humility, patience, conciliation," famously summed the essence of Judaism: "What is hateful to you, don't do to others. This is all the law; the rest is commentary. Now go and study"—and he felt that all men, regardless of social standing, had the right to study. Hillel established the foundations of normative Judaism, and his descendents down to the 5th century held the office of Patriarch of the Palestinian Jewish community. Hillel's descendants included Gamaliel ha-Zaken ("the elder"), teacher of Saul/St. Paul (the Jewish persecutor of Nazarenes/Christians who then became a Nazarene), who apparently was trained in the art of opening to God and experiencing the visionary states of "being raised up to heaven" as part of the merkabah and hekhalot mysticism. Hillel's disciples included Jonathan ben Uziel, a great mystic, yet about whom almost nothing is known, and Johanan (or Yochanan) ben Zakkai (1st cent. CE; Palestine), self-designated as "least of Hillel's disciples," yet the most important Jewish leader after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. In Jerusalem he taught many disciples the subjects of law, homiletics, ethics, and esoteric lore. He is the first sage noted for involvement in merkabah mysticism. Significantly, it was his request of Roman general Vespasian (later emperor Josephus Flavius, according to Johanan's prediction) that the small college at Jabneh near Jerusalem be spared Roman destruction which allowed Judaism to survive and flourish with a new base. "To maintain the Torah without the Temple, Johanan reorganized religious life and worship (now exclusively synagogue-oriented) and re-established a national leadership around the Jabneh religious court. The rabbis were now undisputably the leaders of the people and Johanan worked to construct national unity." (Geoffrey Wigoder, in J. Hinnells [Ed.], Who's Who of World Religions) Johanan's disciples, to whom he taught the mysteries of the Merkava, included Eliezer, Joshua, and Eleazar ben Arakh, "the greatest sages and religious leaders of their time." Akiva/Akiba (Palestine, mid-1st century CE to c135), disciple of Rabbi Joshua, was a master logician, one of the most influential figures in the formative stage of rabbinic Judaism, and "the leading mystic of his time." His academy at B'nai B'rak (not far from present-day Tel Aviv) was filled with thousands of disciples. He collected and organized the massive amount of oral teachings of the 1st century rabbis (tannaim), including his own teachings, a basis for Judah Ha-Nasi's codifying this material into the Mishnah. Several sacred works prominent among later Kabbalists are attributed to Akiva, including the hugely influential mystical work, Sefer Yetzira, though this work most likely dates from later centuries. Akiva supported the Bar Kokhba rebellion against Rome in 132-5 CE; he was imprisoned, though chiefly due to his teaching Torah against the interdict; even in prison he still taught, and was cruelly tortured and martyred by the Romans. Judah ha-Nasi ("the Prince"; 120-89 CE) is esteemed for having edited the collections of teachings from the tannaim into the Mishnah, the work which served as the basis for the further elaborations known as the Gemara, which together constitute the multi-volume Talmud. He is also alleged to have been a recipient of Jewish mystical tradition. Nehuniah ben Hakaneh (1st cent. CE), the greatest esoteric master of his time, alleged author of another early mystical work, the Bahir, started an important Jewish mystical movement, the Hekhalot (Heavenly Palace) School, carried on by his chief disciple Ishmael ben Elisha, to whom many mystical sayings are ascribed; Ishmael was one of the leading sages of Jabneh, so prominent after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Rabbi Meir (2nd cent.) of Palestine, another of the Tanna sages prominent in the Talmud, was a student of Akiva and Ishmael, made many contributions to the halakhah religious law-code, and was hailed for his modesty, holiness, and miracles. Moving along several centuries, Saadya ben Joseph of Fayyum, Egypt (892-942), gaon/head of the Jewish academy in Babylon, the "father of Jewish philosophy," opposed the strict, anti-Talmudic, "letter-of-the-law" Karaism movement. Influenced by Muslim thought and the newly translated Greek philosophical works, he attempted to reconcile reason with revelation while arguing for a beneficent monotheism devoted to YHWH. Bahya ben Joseph ibn Pakuda (11th cent.) of Spain emphasized an ascetic mysticism: detachment from the world, abandonment to G-d, humility, frequent solitude and prayer—very close to the Muslim Sufi ideal of the time—though he kept within the bounds of Torah. Moses ben Maimon or Maimonides (1135-1204), indisputably the greatest thinker of the Jewish tradition, articulated his views in the context of the Muslim-influenced school of Hebrew theology in Spain and then Cairo. Like Philo and Saadya, he did not hold to a literalist interpretation of the Bible, which is prone to imaging G-d in excessively anthropomorphic/humanizing terms (along this line, he did not give much credence to the notions of angels and demons). Maimonides saw the world as created out of nothing, dependent upon the benevolent yet utterly transcendent G-d; in his famous Commentary on the Mishnah, he posited a succinct creed of Judaism, entailing 13 articles: "belief in 1) the existence of the Creator; 2) his unity; 3) his incorporeality; 4) his eternity; 5) the necessity of worshipping him alone; 6) the truth of the words of the prophets; 7) the superiority of Moses to all other prophets; 8) the revelation of the Law [Torah] to Moses at Sinai; 9) the immutability of the Law; 10) the omniscience of G-d; 11) retribution in this world and the next; 12) the coming of the Messiah; and 13) the resurrection of the dead." (Quoted, with adaptations, in Ninian Smart, The Religious Experience of Mankind.) Maimonides, in the tradition of the Neoplatonists and Christian philosopher-theologians like Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (c500 CE) and John Scottus Eriugena (c800-877), and the ancient Upanishad scriptures of India, utilizes a via negativa "negative way" theology to insure that we worship the true God beyond our anthropomorphizing human projections: "The description of God by means of negation is the correct description—a description that is n ot affected by an indulgence in facile language.... With every increase in the negations regarding God, you come nearer to the apprehension of God." Maimonides was highly esteemed and widely read. Yet a certain intellectualism on his part, and his positing of what might seem to lesser minds to be a remote, almost inaccessible G-d (a G-d realizable chiefly by those who could attain to genuine prophecy)—all this would be softened by other thinkers. Thus, Judah ben Samuel Halevi (d.1217), an anti-philosophical poet and pietist who established a rabbinical academy at Regendsburg and was principal author of the classic work of German Jewish holy ones, Sefer Hasidim, emphasized awe and humility in the presence of the living G-d, love of all humans (notable at a time when Jews were subject to harsh persecution) and proper treatment of animals. Judah authored other books, on mysticism and theology, but these are lost to us. Hildai (Hasdai) Crescas (c1340-1412), spiritual and political leader of the Jewish community of Barcelona, Spain, emphasized G-d's great love. Hildai affirmed, in works like Or Adonai (Light of the Lord) that this creation, notwithstanding its apparent flaws and injustices, is an overflowing of G-d's love, and that the way to realize union with G-d is therefore also through love. "Salvation is attained, not by adherence to metaphysical propositions, but by the love of God expressed in action." Maimonides actually also asserted the primacy of love, but had not emphasized it so much in his works, so the views of Judah and Hildai are important in this regard. (Hildai wrote his works expressly as a substitute for Maimonides' works.) Based on the early esotericism of Merkava mysticism, as well as streams of Gnosticism, Neo-platonism, and theosophical Sufism, there began to emerge among the Jewish elite in the 13th century in Spain and Provence, later spreading to Palestine, a variegated movement known as Kabbalah or Cabala (or variants), meaning "received Tradition" of Jewish mysticism. It was an attempt to interiorize Judaism even more strongly. Kabbalah was ushered into the limelight with the ministry of the wide-traveling, Sufi-influenced Rabbi Abraham Abulafia (1240-95) and his followers, and the publication of numerous works said to have first originated in the early Talmudic period (1st-2nd centuries CE). Most important among these mystical tracts was the Zohar (Book of Splendor, written in Aramaic), followed by such works as the Sefer ha'Iyyun (Books of Contemplation), Ma'yan ha Hokhmah (Foundation of Wisdom), Hekhalot Rabatai (The Greater Chambers), Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Formation) and Bahir (Book of Brightness; said to be one of the earliest works, the first to discuss the Sefirot—see below; also elucidating the doctrine of reincarnation). The Zohar, which was claimed to have been originally written in the second century by Rabbi Simon bar Yochai, a disciple of Rabbi Akiba, was actually penned in its current form by Moses de Leon (d. 1305), a native of Granada, Spain. The Zohar declares G-d to be Ain Sof, Endless or Infinite Being, completely without perceivable qualities; out of the Ain Sof arises the world of emanations, part of which is constituted by the ten Divine attributes known as the Sefirot, through which humanity can access the knowable, lovable aspect of G-d. Due to humanity's sins, evil has entered into creation, and the divine presence, Shekhinah, is exiled from the Ain Sof. The task of every Jew, especially every Jewish mystic, is to meditate on the Sefirot and lead a pure, loving, G-d-centered life which thereby will help the Shekhinah reunite with the Ain Sof, and will help liberate the divine sparks in every creature from the "shells" of a desacralized existence, enabling them to return Godward. Kabbalism began to flourish among the Jewish masses due to the influence of the Sufi-influenced Kabbalah school established at Safed, Galilee in the 16th century, especially in the person and teachings of the lofty, nondual philosopher-mystic Moses Cordovero (1522-70) and his disciple Isaac Luria (1534-72), better known as the Ari, whose words (and very Gnostic ideas) were transcribed in many volumes by his disciples, chief of whom was Hayyim Vital Calabrese (1542-1620). The Ari emphasized the doctrines of reincarnation of souls (gilgul neshamot) and the final eschatalogical liberation of the divine sparks in all beings, reunited in G-d. To effect this cosmic restoration (tikkun) the Ari urged his disciples to lead lives of love for G-d, ascetic purity, fasting and the practice of kavanah, meditative chanting of G-d's Name(s). After being quite popular in the 16th century and much of the 17th century, Kabbalist Jewish mystical thinking and practice went underground again after the rise and fall of the unstable Lurianic Kabbalist and pseudo-Messiah, Shabbatai Tzevi (1626-76) of Turkey, who wound up apostatizing to Islam. At this time when Jews were massively depressed due to religious disappointment and intermittent heavy persecution by Christians, a widespread Jewish Kabbalist mysticism arose again in the mid-18th century with the leadership of the amazingly charismatic figure, the Ba‘al Shem Tov (acronym: Besht), the "Master of the Good Name," Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer of Poland/Ukraine (1698-1760). Soon an estimated half of all European Jews were followers of his ecstatically joyous, warmly loving, heroically ascetic, and deeply mystical way of the Hasidim or "Blessed Ones." Hasidism promotes a communal brotherhood engaged in fervent prayer and animated singing, and especially focuses on the person of the tzaddik (plural: tzaddikim), the enlightened saint/sage/master, called rebbe, whose intimate relationship with G-d has a spiritually liberating effect on those who come into proximity with the rebbe, thus the rebbe became a kind of intermediary between G-d and humanity. Hasidism was regarded as a heresy at the time by traditional rabbinic authority, for it "taught that devoutness complements religious observance and that simple faith mitigates the rigid discipline of the Law." Today, despite the loss of so many tzaddikim and their followers to the Nazi Holocaust, Hasidism is flourishing, not only in the state of Israel, but also in Europe and the United States, especially in Brooklyn and other parts of New York. (See other handout for more information on Hasidism and other influential tzaddikim such as Nahman of Bratzlav, Dov Baer of Mezritch, Menahem Mendel, Yaakov Joseph, Pinhas of Koretz, Nahum of Tchernobil, et al.) Moses Mendelssohn (d. 1786), his son Joseph, David Friedlander, David Frankel, and Isaac Euchel, all living in Germany, and Nachman Krochmal, Isaac Baer Levinsohn, Solomon Rappoport and Aaron Libermann in lands further east, were the leading figures who attempted to bring Judaism into relationship with the so-called "European Enlightenment" period of increasing secular-humanism that swept Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. A few of these individuals even thought of merging Judaism into a dogma-free, rationalist form of Christianity. But another wave of anti-Semitism in Europe and Russia led men such as Perez Smolenskin and Moses Loeb Lilienblum in the 19th century to argue for a renewed, distinctive Judaism. As it turns out, the main function of the Enlightenment period was, in the words of one historian, "to serve as a transition from the isolation of traditional Judaism to such movements as religious Reform, Conservatism and nationalism on the one hand, assimilation on the other." A Reform Judaism synagogue first arose in Hamburg, Germany, in 1818, followed by similar synagogues in London, Vienna, Prague, Frankfurt, and Berlin. Practices of Protestant Christianity were often the inspiration for many of the changes, such as using the local vernacular language instead of Hebrew, instituting Sunday worship (the Jewish Sabbath day had, of course, always been on Saturday), abolishing segregation of the sexes in the synagogue, utilizing organ music in the services, and de-emphasizing or eliminating any references to a coming Messiah. Reform Judaism was inaugurated by such thinkers as Rabbi Abraham Geiger, Samuel Holdheim and those other progressive rabbis attending the rabbinical conferences in 1844, 1845 and 1846. In the early 20th century, Claude Montefiore of England and Leo Baeck of Germany helped establish the World Union for Progressive Judaism, and in America, where Reform Judaism would take an even stronger hold, Isaac Mayer Wise was the primary figure (followed by David Einhorn, Samuel Hirsch and Stephen Wise) responsible for establishing this new kind of Judaism, which adhered to timeless, universal religious truths, moral laws, and principles of social justice, de-emphasizing the rituals, historical emphasis, and perceived "backwardness" of traditional Judaism. Conservative Judaism, idealizing preservation and progress, arose in Germany in the mid-19th century as a counter-movement relative to Reform Judaism, and has since then served as a kind of mediating position between Reform and Orthodox Judaism. Led by Zecharias Frankel, it conserved essential aspects of traditional Judaism while maintaining a measure of freedom in the interpretation of Jewish doctrine. Other leading Conservative Jewish teachers/scholars included Adolf Buchler, Isidore Epstein, Solomon Schechter--the major organizer of Conservative Judaism in America, Louis Ginzberg, Hayim Tchernovitz, Louis Finkelstein, Saul Lieberman, Jacob Agus, and the "neo-Hasidic" scholar, Abraham Joshua Heschel. From Conservative Judaism branched Reconstructionism, a community-oriented faith founded by Mordecai Kaplan (d. 1983) in the 1920s. Orthodox Judaism, witnessing these various mystical movements of Kabbalism and Hasidism, and the more humanistic movements of Reform and Conservative Judaism, has not remained silent or stagnant in the last 200 years. Hayyim of Volozhin and Israel Lipkin/Salanter of Lithuania, Samson Raphael Hirsch in Frankfurt, Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935), the chief rabbi in Palestine for much of the first half of the 20th century, Nehama Leibowitz a woman of Jerusalem, one of the greatest Bible teachers in modern Judaism, and the late young prodigy Aryeh Kaplan and also Joseph Baer Soloveichik in America have all brought a fervent holiness and new liveliness to traditional Judaism, which has been amplified by the re-creation of the Jewish nation in the formation of Israel in May, 1948. Meanwhile Hasidism, after being nearly decimated by the Nazis in Eastern Europe in the late 1930s and early 1940s, is still going strong, especially in the Rabinowicz-Monastritsh line descended from Jacob Isaac Rainowicz (d. 1814), the Bratslav Hasidic line descended from Nachman of Bratslav (d. 1810), the Chernobyl Hasidic line from Mordecai Twersky (d. 1837), and the huge Chabad-Lubavitcher sect descended from Shneur Zalman (1745-1813) of Lyady in Belorussia, and represented to great acclaim by the Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-94), who settled with his father and family in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York to lead and develop by far the largest Hasidic organization. (Chabad/Habad has taken on Messianic proportions in the minds of some of the Rabbi's more emotional followers). Neo-Hasidism, which arose with the mystical-existential views of Martin Buber, is particularly strong in the Jewish Renewal movement, exemplified in the ministries of contemporary rabbis in America led by Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Joseph Gelberman, Sholomo Carlebach, Philip Berg, David Cooper, Jonathan Omer Man, and David Din. Arthur Green is the leading scholar-theologian of this movement, which combines a deep spirituality with a strong sense of social, economic and environmental justice. Judaism definitely shows signs of renewal, not decay, though many Jewish rabbis are concerned about the weakening or even eventual decline of the faith outside Israel as a result of intermarriage with non-Jews. One of the more promising developments in Judaism is the acceptance into the rabbinate of women in Reform, Conservative, and neo-Hasidic Jewish circles. These and other women fully join with their brothers in celebrating, thanking, and aspiring further in communion with the One G-d, the Ultimate Holy Mystery and Source of all Grace.

IMPORTANT TERMS Tetragrammaton (Greek)--refers to the four letters comprising the name of God: YHWH or YHVH (Yahweh) or JHWH (Jahweh); these letters are often the object of Jewish mystical meditation. Adonai--the Lord; the term Jews use to address God. Shekhinah--God's Glory, the indwelling presence of God on earth; in Kabbalah it is described in feminine terms as the aspect of God identified with the tenth sefirah, Malkhut, and which, with the fall of humanity, has been exiled into the world; a major emphasis in Jewish spiritual practice is to help redeem the exiled Shekhinah by returning to union with God. Merkava / Merkabah--God's lofty "Chariot" or Throne of Glory (as first described in Ezekiel); sometimes in rabbinic literature there is a distinction between God's throne of Mercy and throne of Justice, each of which expresses a divine function befitting the state of humanity and the earth. Ain Sof (En Soph)--the Endless, Boundless, Infinite Being of the Godhead, completely formless and transcendent. Ain (Ayin, Ein, En)--"No-thing-ness," the highest level of Divine transcendence. Atzilut--the "universe" of No-thing-ness or Nearness (to Godhead); this is the highest of the four universes in an oft-used Kabbalah schema; the other three (in descending order) are Beriyah (creation; thought), Yetzirah (formation; speech), and Asiyah (making or action). Sefirot (pl.) / Sefirah (sing.)--(Kabbalah concept:) the ten Divine emanations or creative powers by which G-d directs the universe; they come together in the lowest one, Malkhut, Kingship, associated with the Divine Presence, Shekhinah. The other nine Sefirot (which are graphed in a kind of "tree") are Yesod, Foundation; Hod, Splendor; Netzach, Victory; Tiferet, Beauty; Gevurah, Strength; Chesed, Love; Binah, Understanding; Chokhmah, Wisdom; and Keter, Crown, the highest Sefirah. The Sefirot were probably first discussed in the Bahir (Book of Brightness), one of the oldest Kabbalah texts, said to be written by Rabbi Nehuniah (1st century CE), the greatest esoteric master of his time, but most likely not penned until the early 1200s. Daniel Matt has told how the idea of the Sefirot was controversial; whereas the more careful proponents of the sefirot saw them as ultimately mere symbols of the indivisible, ineffable Divine One in its mysterious process of emanation and return, critics saw them as a form of polytheism. Abulafia noted that some adherents of the sefirot had outdone Christian trinitarians, turning God into ten! But kabbalists insist the Ain Sof and sefirot are nondually one, a unity. Tannaim (Tanna, singular)--the "repeaters" or masters of the Mishnah literature, the first part of the Talmud. Amoraim (Amora, sing.)--the sages of the second Talmudic period (3rd-6th century CE), who originated the Gemara portion of the Talmud. Maggidim (Maggid, sing.)--preachers; they were sometimes itinerant, sometimes regulars in the community. Tzaddikim (Tzaddik, sing.)--the "righteous ones," Hasidic sages or rebbes. Hasidim (Hasid, sing.)--the "devout," those who practice hasidut, piety or loving concern; hasidim is a term which was first used to denote members of some devout brotherhoods of the Talmudic era, then later a 13th century mystical, ascetical German Jewish group, but is primarily used to designate the fervent mystical group which arose in central Europe under the leadership of the Ba'al Shem Tov, Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, in the first half of the 18th century. (The hasidim were opposed as heretical by the more orthodox mitnagdim as well as by those modernizing Jews sympathetic with the European Enlightenment). Rosh Yeshivah--Dean of a Talmudic school (yeshiva). Bar/Bat Mitzvah--"son/daughter" of commandment, a boy or girl who, upon completion of the 13th year, accepts responsibility of fulfilling the Law; the term also refers to the celebration of this event. Melammed--teacher of the Torah to young children. Shabbat / Sabbath--the special day of rest, prayer, friendship and family closeness, beginning Friday evening, extending through Saturday night, observed on Friday with a special dinner (including challah, special braided bread) and the lighting of candles, and ended on Saturday night with another ceremony, the havdala. Borkhu (literally: "Bless the Lord")--the call to prayer by the prayer-leader (shaliah tzibur). Minyan--the quorum of ten adult males which is the minimum number of people required for Jewish community worship. Talit--the prayer shawl worn by the Jew, worn so as to cover the head as much as possible. Tefillin--the phylacteries, or leather cubicles containing scriptural texts inscribed on parchment, the sign of the covenant between G-d and Israel; they are attached to the left arm and head during the weekday morning service. Shaharit--morning religious service. Minhah--afternoon prayer. Ma`ariv--the evening religious service. (Jews are required to pray at least 3 times daily.) `Amidah (literally: "standing")--the core of the Jewish prayer service, recited standing 3 times daily. Hallel--"praise"; a group of psalms recited in the prayer service at certain festivals. Sh'ma yisrael--the declaration of monotheistic faith in God derived from Deuteronomy 6:4, recited 2x daily (Sh'ma Israel, Adonai Elohenu, Adonai Echod, "Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One!") Amidah / Shemonah Esreh--the collection of 18 (or 19) blessings repeated thrice daily; this prayer was composed by the Great Assembly of Jewish rabbis just before the close of the prophetic period in the early centuries BCE. Selihah--penitential prayer. Yihud--prayer designed to proclaim (and in Kabbalah, to bring about) the unity of G-d and Shekhinah. Ana' Bakoah--the mystic prayer based on the kabbalistically derived 42-letter name of G-d. Davenen--Yiddish term, "to pray," fervently and as often as possible, say the Hasidim. Hitbodedut--the Kabbalist term for meditation; from the root term badad, "to be secluded"; there are two forms of seclusion, external and internal; the internal is the more important for real meditation. Mechikah--erasure, a meditative method (in the school of Abulafia) of erasing all images from the mind. Kavanah (kavanot, pl.)--"intention" or "devotion," the intention directed towards God while performing a religious activity; in the Kabbalah, kavvanot are the permutations of the divine name that aim at overcoming the separation of forces in the upper world; these are chanted meditatively like mantras; optimally, this meditative chanting culminates in hitpashtut hagashmiut, a divestment of the sense of the physical and realization of the spiritual. Yechudim--the method of "unifications" as emphasized by the Ari (Isaac Luria); a kind of inner visualizing of various combinations of divine names. Mitzvah--a divine commandment and, when fulfilled, a good deed. There are 613 mitzvot in the Torah. Yir'at shamayim--the "fear" or "awe" one experiences in the face of God's great holiness, purity, and mystery; this kind of piety is the central attitude stressed in the Torah. Teshuvah--an individual's repentance or turning from aberration to the "way of God." Ruach HaKodesh--the "Holy Spirit"; a general Hebraic term for enlightenment. Kodesh--divine holiness. Devekuth--attachment or cleaving to God; a term for God-realization or enlightenment. Hitlavahut--a state of spiritual ecstasy, characteristic of the tzaddikim and hasidim. Gadlut--a state of expanded spiritual consciousness; contrasted with katnut, a state of constricted spiritual consciousness. Halakhah--Jewish law/legal decisions; literally, "the way to walk." Haggadah--"narrative," the collection of sayings, folklore, historical knowledge, theological arguments, ritual traditions, and hymns pertaining to the exodus from Egypt, recited in the home service on Passover night. Menorah--the seven-branched candelabra, especially the one used in the synagogue. Matzah (matzot, pl.)--the unleavened bread, eaten during the week of Passover. Shofar--the ram's horn, sounded in the synagogue, primarily on New Year's day; the sound of this horn reminds Jews of the Divine revelation at Mt. Horeb and Mt. Sinai, and will supposedly be heard again at the time of the coming of the Messiah. Mikveh--ritual bath; especially important to the Hasidim; it's considered best to bathe in a natural body of water. Sheol--the most common name in early Judaism for that region inhabited by the dead; in the earliest phase of Jewish literature, consciousness does not continue after death; later (with Enoch & Elijah) one begins to hear passages suggesting that G-d may save an individual from sheol and take the individual to Himself (e.g., Gen. 5:24; II Kings 2:11; Ps. 49:16; I Sam. 2:6). Still later (e.g., Dan. 12:2) clear allusions to resurrection of the dead may be found. Gan eden--a Talmudic concept, the garden of delight where pious souls enjoy communion with the glorious light of the Shekhinah, Divine Glory; righteous, non-idolatrous Gentiles may also enjoy this post-mortem realm, for they are considered true Israelites by their faith in YHWH. Gehenna--a Talmudic concept, the burning pit in which the unrighteous are punished after death. Olam ha-Tohu--Kabbalist concept of the realm in which souls exist after death before their redemption. Olam ha-Dimyon--Kabbalist concept of the realm for straying souls of persons who died deluded by their vanity. Shedim / Mazzikin--the "demons" or "harmful ones," said to be the offspring begotten by the "giants mating with the daughters of men" (Gen 6:1-4); legends about sages encountering and besting demons have occurred in the Talmud and Kabbala literature; incantations and amulets have been used as protection against them; some scholars, from at least the time of Maimonides have denied their existence; yet a number of other leading scholars have affirmed their existence and advised the people how to avoid or triumph over them. Kelipot--the "shells" or forces of evil or desacralization.

A Select Bibliography on Judaism On ancient Judaism, see Thomas Thompson, The Mythic Past: Biblical Archeology and the Myth of Israel, NY: Basic Books, 1999; Niels Peter Lemche, Prelude to Israel’s Past: Background and Beginnings of Israelite History and Identity (E.F. Maniscalco, Tr.), Hendrickson, 1998; Donald Harman Akenson, Surpassing Wonder: The Invention of the Bible and the Talmuds, Harcourt Brace, 1998; and Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? HarperSF, 1997; Gary Geenberg, Bible Myth: The African Origins of the Jewish People, Citadel, 1998. For the Tanakh scripture, see Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures, Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1988; the new JPS translation according to the Traditional Hebrew Text (excellent, modernized, sensitive rendition).

Other works, with an emphasis on Jewish mysticism, include: Abelson, Joshua, Jewish Mysticism: An Introduction to Kabbalah, Hermon, 1981. Afterman, Allen, Kaballah & Consciousness, Sheep Meadow, 1992. Ariel, David, The Mystic Quest: An Introduction to Jewish Mysticism, NY: Pantheon, 1992. Barnstone, Willis, The Other Bible, SF: Harper & Row, 1984 (a 740 page work on the Colecao Cabala). Baron, S.W., The Social and Religious History of the Jews, 12 vols., Oxford, 1952-1967; The Jewish Community: Its History and Structure to the American Revolution, 3 vols., Philadelphia, 1942. Besserman, Perle (Ed.), Teachings of the Jewish Mystics, Shambhala, 1998. Bischoff, Eric, The Kabbala: An Introduction to Jewish Mysticism & Secret Doctrine, Samuel Weiser, 1985. Bloom, Harold, Kabbalah and Criticism, Continuum, 1983. Blumenthal, David, Understanding Jewish Mysticism: The Philosophic-Mystical Tradition & the Hasidic Tradition, 2 vols., Ktav, n.d. Bosker, Ben Zion, The Jewish Mystical Tradition, NY: Pilgrim Press, 1981; and Bosker (Tr.), Abraham Isaac Kook: The Lights of Penitence, The Moral Principles, Lights of Holiness, Essays, Letters, and Poems, NY: Paulist, 1978 (Rabbi Kook [1865-1935] was the chief rabbi of Palestine before the nation of Israel was born, a true mystic & spiritual master). Buber, Martin, Tales of the Hasidim (Olga Marx, Trans.), NY: Schocken Books, 1991/1947 (originally 2 vols., now in one volume); The Way of Man, London, 1950; NY: Citadel Press 2nd ed., 1967; Hasidism and Modern Man (Maurice Friedman, Ed. & Tr.), Humanities ed., 1988; The Legend of the Baal-Shem, Schocken, 1987; I and Thou (Walter Kaufman, Tr.), NY: C. Scribner's Sons, 1970 (Buber brought widespread attention to Hasidism, interpreting it with an especially mystical and existential flavor). Buxbaum, Yitzhak, Jewish Spiritual Practices, Aronson, 1990 (comprehensive 500 pages); and Buxbaum, The Light and Fire of the Baal Shem Tov, NY: Continuum, 2005. Carlebach, Shlomo, Holy Beggar Teachings: Jewish Hasidic Stories, Maimes, 1979; Yitta Halberstam Mandlebaum, Holy Brother! Inspiring Stories and Enchanted Tales of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, Aronson, 1999, Shlomo Carlebach, The Reb Shlomo Songbook; Shlomo Carlebach & Kalman Serkez (Eds.), The Holy Beggars’ Banquet: Traditional Jewish Tales and Teachings of the Late, Great Reb Shlomo Carlebach and Others, Aronson ed., 1998; Meshulam Brand, R. Shlomole: The Life and World of Reb Shlomo Carlebach (available from POB 6743, Efrat IL, 90435 and from the website www.shamash.org/judaica/reb-shlomo/index.html). Cooper, David, God Is A Verb: God and the Practice of Mystical Kabbalah, Riverhead, 1997. Dalfin, Chaim, To Be Chasidic: A Contemporary Guide, Aronson, 1997. Dan, Joseph, & Kiener, Ronald (Eds.) The Early Kabbalah, NY: Paulist, 1986 (fine scholarship). Daum, Menachem, & Oren Rudavsky, “A Life Apart: Hasidism in America” (documentary film for television), 1997. Davis, Avram, The Way of Flame: A Guide to the Forgotten Mystical Tradition of Jewish Meditation, HarperSF, 1996; Avram Davis & Manuela Dunn Mascetti, Judaic Mysticism, Hyperion, 1997. Dresner, Samuel, Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev, NY: Hartmore, 1975; The Zaddik, Schocken ed., 1974. Eban, Abba, Heritage: Civilization and the Jews (film), 1984; see also his book of the same name, published by Summit, 1984. Eisenberg, Robert, Boychiks in the Hood: Travels in the Hasidic Underground, HarperSF, 1995. Eisenman, Robert & Michael Wise (Ed.& Trans.), The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered, London: Element Books, 1992 (on the writings of the famous Qumran ascetic Jewish community which flourished around the time of Christ). Epstein, Perle, Kabbalah: The Way of the Jewish Mystic, Boston: Shambhala, 1988 (excellent work by a female scholar, a descendant of the Baal Shem Tov). Fine, Lawrence, Safed Spirituality: Rules of Mystical Piety, The Beginning of Wisdom, NY: Paulist Press, 1984. Finkel, Avraham Yaakov, Contemporary Sages: The Great Chasidic Masters of the Twentieth Century, Aronson, 1994. Gelberman, Joseph, To Be ... Fully Alive, Farmingdale, NY: Coleman Graphics, 1983, Reaching a Mystical Experience: A Kabbalistic Encounter, NY: Wisdom Press, 1970, The Kabbalah As I See It, 1997, Pearls and Wisdom, 1999, and his 4-part video series, “The World of the Kabbalah” (last three items available from bookstore section of Gelberman’s website: www.interfaith.org) Gershom, Yonassan, Beyond the Ashes: Cases of Reincarnation from the Holocaust (Jon Robertson, Ed.), Virginia Beach, VA: A.R.E. (Assoc. for Research and Enlightenment) Press, 1992; From Ashes to Healing: Mystical Encounters with the Holocaust, A.R.E., 1996; and Jewish Tales of Reincarnation, Aronson, 1999. Glotzer, Leonard, The Fundamentals of Jewish Mysticism: The Book of Creation & Its Commentaries, Aronson, 1992. Goldin, Judah, The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan, Yale Univ. Press, 1990; The Living Talmud: The Wisdom of the Fathers, Chicago, 1958. Green, Arthur & Barry Holtz (Eds.), Your Word Is Fire: The Hasidic Masters on Contemplative Prayer, Schocken, 1987; Arthur Green (Ed.), Jewish Spirituality, Vol. 1: From the Bible Through the Middle Ages; Vol. 2: From the Sixteenth-Century Revival to the Present, Crossroad, 1986, 1988; Keter: The Crown of God in Early Jewish Mysticism, Princeton Univ. Press, 1997 (fine works by a great scholar). Greenberg, Sidney (Ed.), Light from Jewish Lamps: A Modern Treasury of Jewish Thoughts, Aronson, 1986. Gurary, Noson, Chasidism: Its Development, Theology and Practice, Aronson, 1997. Halevi, Z'ev Ben Shimon, Psychology and Kabbalah, 1987; School of Kabbalah, 1986; The Work of the Kabbalist, 1985; and The Way of the Kabbalah, 1976, all published by Samuel Weiser; and Kabbalah: Tradition of Hidden Knowledge, Thames Hudson, 1980 (well-illustrated). Harris, Lis, Holy Days: The World of a Hasidic Family, Macmillan, 1986. Heifetz, Harold (Ed.), Zen and Hasidism, Wheaton, IL: Quest, 1978 (good anthology) Heschel, Abraham Joshua, The Circles of Baal Shem Tov: Studies in Hasidism (S.H. Dresner, Ed.), Univ. of Chicago, 1985; Quest for God, NY: Crossroad ed., 1982; A Passion for Truth, NY: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1973; God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1976/1956 (by a beloved scholar and rabbi of Hasidic Judaism). Hirsch, Solomon, Nineteen Letters of Ben Uziel: A Spiritual Presentation of the Principles of Judaism (B. Drachman, Tr.), Shalom, n.d. Hundert, Gershon (Ed.), Essential Papers on Hasidism, NYU Press, 1990 (extensive, scholarly essays). Idel, Moshe, Kabbalah: New Perspectives, Yale U. Press, 1988; The Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia, State Univ. of NY, 1987; Studies in Ecstatic Kabbalah, SUNY, 1988 (excellent works). Jacobs, Louis, Jewish Mystical Testimonies, Schocken, 1996. Joseph, Dan (Tr.), The Early Kabbalah, Paulist, 1986. Kamenetz, Rodger, Stalking Elijah: Adventures with Today’s Mystical Masters, HarperSF, 1997, and The Jew in the Lotus: A Poet’s Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist India, HarperSF, 1995. (The first title is an excellent overview of the Jewish Renewal movement in the USA.) Kaplan, Aryeh, Meditation and Kabbalah, York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1982; Meditation and the Bible, Weiser, 1978; The Light Beyond: Adventure in Hassidic Thought, Maznaim, 1981; The Handbook of Jewish Thought, Maznaim; Immortality, Resurrection & the Age of the Universe: A Kabbalistic View, KTAV, 1990; Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Creation), Weiser paper ed., 1997; Kaplan (Ed. & Tr.), The Bahir, S. Weiser, 1979 (this late young prodigy was one of the most insightful and pioneering writers today on the subject of Jewish meditation & mysticism). Kenton, Warren, Kabbalah: Tradition of Hidden Knowledge, London: Thames & Hudson, 1979 (illus.) Kushner, Lawrence, The River of Light: Spirituality, Judaism, Consciousness, Jewish Lights, rev. ed., 1990. Labowitz, Shoni, Miraculous Living: A Guided Journey in Kabbalah through the Ten Gates of the Tree of Life, Simon & Shcuster, 1998. Landau, David, Piety and Power: The World of Jewish Fundamentalism, Hill & Wang, 1993 (fine work by a prominent Israeli newspaperman on various forms of mystical and non-mystical orthodox Judaism in Israel today). Landman, Isaac (Ed.), The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, NY: Univ. Jewish Encyc. Inc., 1942. Langer, Jiri, Nine Gates to the Chasidic Mysteries, Aronson, 1993. Leibowitz, Nehama, various works in xerox form (before her passing, the most popular Bible teacher in modern Israel). Lerner, Michael, Jewish Renewal: A Path to Healing and Transformation, Putnam’s Sons, 1994. Loewenthal, Naftali, Communicating the Infinite: The Emergence of the Habad School, U. of Chicago, 1990. Luria, Kitve Ari, Hebrew Text (18 vols), Research Center on Kabbalah, 1985. Luzatto, Moshe, Derech HaShem: The Way of G-D (Aryeh Kaplan, Tr.), Feldheim, 1978. Matt, Daniel, The Essential Kabbalah: The Heart of Jewish Mysticism, HarperSF, 1996. Melton, Gordon (Ed.), Encyclopedia of American Religions, Detroit: Gale Research (see most recent edition; see entries on Judaism; good info source on lineages of Hasidism up to the present time). Menahem Nahum of Chernobyl: Upright Practices, The Light of the Eyes (Arthur Green, Tr.), Paulist, 1982. Mintz, Jerome, Legends of the Hasidim: An Introduction to Hasidic Culture & Oral Tradition in the New World, Univ. of Chicago Press, 1974 (a massive scholarly work). Myer, Isaac, Qabbalah: The Philosophical Writings of Solomon Ben Yehudah Ibn Gabirol, Gordon Press, 1975. Neusner, Jacob, A Life of Yohanan ben Zakkai, Leiden: Brill, 1962; Theology of Normative Judaism: A Source Book, Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005; An Introduction to Judaism: A Textbook and Reader, Westminster John Knox, 1992; Between Time and Eternity: The Essentials of Judaism, Wadsworth, 1975; The Religious Study of Judaism, 4 vols., Univ. Press of America; Judaism: The Evidence of the Mishnah, U. of Chicago, 1981; The Incarnation of God: The Character of Divinity in Formative Judaism, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1988; A Rabbi Talks with Jesus: An Intermillennial, Interfaith Exchange, Montreal: McGill U. Press, 2nd ed., 2000; Judaeo-Christian Debates: God, Kingdom, Messiah, (with Bruce D. Chilton), Minneapolis: Fortress, 1998; How the Rabbis Liberated Women, Atlanta: Scholars' Press, 1999; and a multitude of other works (Neusner is hugely prolific, having authored or edited over 920 works, and having translated into English nearly the entire Rabbinic canon, though some of his analysis of Talmud has been questioned by other scholars). Nigal, Gedalyah, Magic, Mysticism and Hasidism: The Supernatural in Jewish Thought, Aronson, 1994. Ochs, Vanessa, Words on Fire: One Woman's Journey into the Sacred, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990 (fine account, from a feminist perspective, of Judaism in Israel). Patai, Raphael, The Hebrew Goddess, Waynes State U. Press, 3rd rev. ed., 1990. Peters, F.E., Judaism, Christianity, & Islam: The Classical Texts & Their Interpretations, 3 vols., U. of Princeton, 1990. Plaskow, Judith, Women & Judaism: Judaism from a Feminist Perspective, HarperSF, 1991. Rabinowicz, Harry, Hasidism: The Movement & Its Masters, Aronson, 1988. Rabinowicz, Tzvi, The Encyclopedia of Hasidism, Aronson, 1996; Tuvi Rabinwicz, Chassidic Rebbes: From the Baal Shem Tov to Modern Times, Targum, 1989. Rosman, Moshe, Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Ba‘al Shem Tov, Berkeley: Univ. of Calif. Press, 1996; Rosoff, David, Safed, the Mystical City, Feldheim, 1991 (Safed was a leading Kabala center). Sanders, E.P., Judaism: Practice and Belief 63 B.C.E.—66 C.E., Trinity, 1992; Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman, Shohama Harris Wiener & Jonathan Omer-Man, Worlds of Jewish Prayer: A Festschrift in Honor of Rabbi Zalman M. Schachter-Shalomi, Jason Aronson, 1994; Zalman Schacter, Gate to the Heart: An Evolving Process, Philadelphia: Aleph, 1993; Paradigm Shift: From the Jewish Renewal Teachings of Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Aronson, 1993; Spiritual Intimacy: A Study of Counseling in Hasidism, Aronson, 1991; Schachter & various co-authors, Sparks of Light, Shambhala, 1983; The First Step, Bantam, 1983; The Dream Assembly, Amity House, 1987; etc. (Reb Zalman was a leading figure in the American Jewish Renewal movement.) Schneider, Susan Weidman, Jewish and Female: Choices and Changes in Our Lives Today, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1984. Scholem, Gershom, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, NY: Schocken, 1941; On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism (Ralph Manheim, Trans.), Schocken, 1965; Kabbalah, Dutton, 1978; On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead: Basic Concepts in the Kabbalah, Shocken, 1991; Origins of the Kabbalah (R. Werblowski, Tr.), Princeton U. Press, 1990; Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah (Werblowski, Tr.), Princeton, 1973; On Jews & Judaism in Crisis, Schocken, 1989; and Scholem (Ed.), Zohar--The Book of Splendor: Basic Readings from the Kabbalah, Schocken, 1987 (Scholem was for many years considered the premiere scholar on Kabbalah & Jewish mysticism, though he was rather intellectual, evidently not a practitioner of Kabbalistic meditation himself). Schweid, Eliezer, Judaism & Mysticism According to Gershom Scholem: A Critical Analysis & Programmatic Discussion (David Weiner, Tr.), Scholars Press, 1985. Sheinkin, David, The Path of the Kabbalah (E. Hoffman, Ed.), NY: Paragon, 1986. Solomon, Norman, Judaism & World Religion, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1991. Spector, Sheila, Jewish Mysticism: An Annotated Bibliography on the Kabbalah in English, Garland, 1984 (important reference work, if already somewhat dated). Steinsaltz, Adin, The Essential Talmud, Harper Collins Basic Books, 1976; In the Beginning: Discourses on Chasidic Thought, Aronson, 1992; The Thirteen Petalled Rose, NY: Basic Books, 1980 / Aronson, 1992. Stone, Michael & David Satran (Eds.), Emerging Judaism: Studies on the Fourth & Third Centuries B.C.E., Augsburg Fortress, 1988. Suarez, Carlo, Song of Songs: Canonical Song of Solomon Deciphered According to the Original Code of Qabala, Shambhala, 1972. Uffenheimer, Rivka Schatz, Hasidism as Mysticism: Quietistic Elements in Eighteenth Century Hasidic Thought, Princeton Univ. Press, 1993. Umansky, Ellen, & Diann Ashton (Eds.), Four Centuries of Jewish Women's Spirituality, Boston: Beacon, 1992. Urbach, Ephraim, The Sages: Their Concepts & Beliefs, HUP, 1987. Verman, Mark, The Books of Contemplation: Medieval Jewish Mystical Sources, SUNY, 1992 (excellent academic work on the Sefer ha'Iyyun and the Ma'yan ha Hokhmah). Weiner, Herbert, 9½ Mystics: The Kabbala Today, NY: Collier Books ed., 1971 (fascinating account of mystical Judaism in Israel in early- to mid-20th century). Weingrod, Alex, The Saint of Beersheba, Albany, NY: S.U.N.Y., 1990. Wiesel, Elie, Sages and Dreamers: Biblical, Talmudic, & Hasidic Portraits and Legends, NY: Summit, 1991; Souls on Fire: Portraits and Legends of Hasidic Masters, Random House, 1972 (these are just two works by a leading Jewish scholar, author, and sage, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize). Wigoder, Geoggrey (Ed. in Chief), The Encyclopedia of Judaism, NY: MacMillan, 1989. Wineman, Aryeh, Beyond Appearances: Stories from the Kabbalistic Ethical Writings, JPS, 1988. Winston, David (Tr.), Philo of Alexandria: The Contemplative Life, the Giants, & Selections, Paulist, 1981. Wolf, Laibl, Practical Kabbalah: A Guide to Jewish Wisdom for Everyday Life, NY: Three Rivers, 1999 Zohar: The Book of Enlightenment (Daniel Matt, Tr.), Paulist, 1983 (a seminal Kabbalist work, written in Aramaic by Moses de Leon, in a densely symbolic, enigmatic style).

On the specific Lubavitcher tradition of Chabad/Habad Hasidic Judaism and its powerful modern expression, see Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Toward a Meaningful Life: The Wisdom of the Rebbe (Simon Jacobson, Ed.), Harper, rev. ed., 2004; Letters by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Brooklyn, NY: Kehot Publication Society, 1979; and the journal Talks and Tales (770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213); and see Rabbi Faitel Levin's book on M.M. Schneerson's radical theology, Heaven On Earth: Reflections on the Theology of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Merkos L'Inyonei Chinuch, 2002 (see website by Max Kohanzad on this radical mystical theology). See the main work by Habad’s founder, Shne’ur Zalman, Tanya’, Kehot, 1956; and see Rachel Elior, The Paradoxical Ascent to God: The Kabbalistic Theosophy of Habad Hasidism (J. Green, Tr.), SUNY, 1992; Abraham Foxbrunner, HABAD: The Hasidism of R. Shneur of Zalman, Jason Aronson ed., 1993; Naftali Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite: The Emergence of the Habad School, Univ. of Chicago, 1990; Louis Jacobs, Seeker of Unity, NY, 1966; Reuven Alpert, God’s Middlemen: A Habad Retrospective: Stories of Mystical Rabbis, White Cloud Press, 1998, with a very valuable 48-page introduction to Habad's history and philosophy by Bezalel Naor. |