|

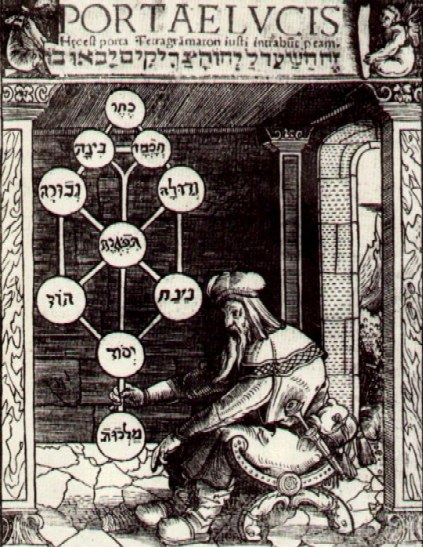

Kabbalah and Hasidism: The World of Jewish Mysticism© Copyright 1999/2005 by Timothy ConwayGrowing numbers of Jews have become deeply interested in mysticism,[1] specifically in the medieval Jewish insights, prayer practices, and solitary meditation disciplines (hitbodedut) that comprise the powerful and influential mystical way of Kabbalah (Qabbalah, Cabala). According to scholars led by the eminent Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (“received tradition”) began to be esoterically promulgated in the second half of the 12th century in the Provence region of southern France by a few leading rabbis—e.g., Rabad of Posquières, Ya‘aqov the Nazirite and Moses Nahmanides. Kabbalah emerged publicly in the early 13th century in the work of the Rabad’s son (Yitshaq the Blind) and in obscure texts like the Sefer ha-Bahir. In Spain there appeared in the 1280s the most important “canonical” Kabbalist book, the Zohar. This mystical novel, now known to be a compilation of booklets penned and in parts even trance-channeled via automatic writing by Moses de Leòn, combined Torah, Midrash (commentary works), theosophy, homily and mythical fiction. Spanish rabbi Abraham Abulafia (1240-95), an extremely influential “ecstatic Kabbalist,” traveled through the Mediterranean as far as Palestine, teaching meditation methods, especially recitation of Divine names and visualized combinations of Hebrew letters. After the unconscionable expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal in 1492/1497 by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, Kabbalah’s primary sphere of influence migrated, first to Jerusalem, then to Safed, Galilee, where it flourished under the leadership of eminent spiritual masters Moses Cordovero (1522-70) and the Ari, Isaac Luria (1534-72), and their disciple Hayyim (Chaim) Vital (1542-1620). Kabbalah combines 1) an early Jewish practice of visualizing the Merkabah or “Divine Throne” (re: Isaiah 6:3 and first chapter of Ezekiel) and Hekhalot or “Heavenly Palace/Hall”; 2) a holy white magic invoking the ten Divine emanations known as Sefirot, and concentrative meditation (kavvanah) upon permutations of the Divine Name, along with “unification” visualizations (yechudim) of these; and 3) a neo-Platonic contemplative meditation on the purely transcendental formlessness of YHVH, the ‘Ayin (No-thingness) or ‘Ein Sof (Boundless/Infinite).[2] The aim of the kabbalist (plural: m’kubalim), expressed in mythical terms, is to purify consciousness through piety, prayer and sacred intention so that the Divine “sparks” (neshâmah) in all creatures will be redeemed from the “shells” (kelipot) of desacralized existence and enabled to return home to God. Through this “raising of the sparks,” the Immanent Divine Glory or Presence (Shekhinah) is liberated from Her exile back into union with the sefirot-aspect of God known as Tif’eret. (This union is symbolically expressed by Kabbalists in openly sexual images of a bride coming to her husband, to the chagrin of rationalist modern Jews and mystics interested in the formless, transpersonal Divine.) In other words, Kabbalah represents a radical way of clearing, sublimating and interiorizing attention so that one becomes a conduit (“pipe,” zinor) for a Divine field of blessing love and healing power (berakhah) that helps restore all creation into the radiant “image and likeness of G-d.”[3] After being covert for much of this century, known only to a few mystics and post-war Israeli scholars, Kabbalah in the last two decades has sprung forth from its hidden recesses through the increasingly public work of these mystics and scholars in conjunction with the curious diggings of Jewish Baby Boom seekers looking for a deeper connection to their tradition. Today Kabbalah, ranging from a purely contemplative practice to a rather superstitious magic (replete with amulets and omen-mongering), enjoys growing popularity among Jews of various camps, in Israel and the West. A survey by Ma‘ariv, the major Israeli newspaper, reported in Fall 1997 that 18% of Israelis, including leading politicians on the right, sought counsel from kabbalistic rabbis, most renowned of whom was Iraqi-born centenarian Harav Yitzhak Kadouri (c1890-2006), a Sephardic rabbi. Many believers carry Kadouri amulets, key chains and blessing cards. (Meanwhile, to rabbis’ chagrin, another 20% of Israelis consult fortune tellers using palmistry, tarot cards or tea leaves; another 11% prefer astrologers). Two months later in 1997, Time magazine identified Kabbalah as a “pop” trend in the USA, with some 200 small-scale programs of experiential Jewish mysticism to be found nationwide.[4] World-renowned pop star Madonna embraced kabbalah—much to the chagrin of old Rabbi Kadouri, who stated “It is forbidden to teach a non-Jew Kabbalah.” With such notoriety, this variegated system received even greater exposure among the youth. Just as in Christianity the return to a more mystical, meditative path has been in large part stimulated by Christians exploring Eastern spiritual paths, so also much (not all) of the impetus for interest in mystical Judaism has come from Jews who have explored—or seen many of their friends and family exploring—meditation-oriented traditions like Theravada, Zen and Vajrayana Buddhism, Hindu Vedanta and Muslim Sufism.[5] In fact, with the Kabbalistic emphasis among Hasidic rebbes on meditation, reincarnation (gilgul neshamot)[6] and the possibility for sublime union with G-d (devekut), mystical Judaism can strongly vie with Eastern religious traditions for “market share” in the case of Jews, especially younger ones, who might otherwise only be interested to explore these Eastern religious traditions. Leading neo-Hasidic rabbis of our day bringing a contemplative Kabbalist Judaism to would-be mystics include, in Israel, Rabbi Joseph Schechter, who from the 1960s on led a youthful community in a meditative, purificatory Jewish spirituality drawing on Kabbalah, Hasidism, Hindu and Taoist meditation, parapsychology, etc. Polish-born Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, who trained within the ultra-orthodox Lubavitcher Hasidism line, studied assorted non-Jewish mystical spiritual paths and in 1962 founded his quasi-Hasidic B’nai Or (“Children of Light,” now P’nai Or, “Faces of Light”) Religious Fellowship, headquartered in Philadelphia. Through this organization Rav Zalman introduced numerous American Jews to meditation and has become a leading liberal prophet of the Jewish Renewal movement in America, having ordained scores of rabbis and influenced many others. Rabbi Joseph Gelberman’s “Little Synagogue” Hasidic community in New York has also brought considerable Eastern spiritual influences to American Jews, resulting in a strong appreciation for meditation and mystical depth within a Jewish context. Gelberman, like Rav Zalman, has been quite active in the interfaith movement and in this way has helped fellow Jews to draw on the best of other traditions to enrich their own path of love for G-d. Rabbi Jonathan Omer-Man is a prominent, eloquent Kabbalist in Los Angeles, and Rabbi David Cooper authored a best-seller primer on Kabbalah; he teaches, along with his wife, a growing group of students in Colorado.[7] More generally, the works of Abraham Joshua Heschel, Gershom Scholem, Martin Buber, Elie Wiesel, Moshe Idel, Aryeh Kaplan, Arthur Green, Daniel Matt and Rodger Kamenetz have stimulated a revival of meditative Jewish spirituality among countless Jews and edified many of us lovers of Jewish lore who adhere to other traditions. Significantly, disproportionate numbers of Jews are to be found leading and attending various American Buddhist and, to a lesser extent, American Vedanta and Sufi meditation circles. Some would put this figure as high as one-third, a figure that shocks traditional Jews, who consider any involvement in non-halakhah forms of religion to be avodah zarah, forbidden religious service, or even minut, apostasy.[8]

The Continued Strength of Mystical Hasidism The study and practice of the Kabbalah’s mystical way has been central among the orthodox Hasidic Jewish congregations. These descend from the work of Hasidism’s illustrious founder, the extraordinary spiritual master of Podolia (western Ukraine), Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer —the Ba‘al Shem Tov (“Master of the Divine Name”; 1698-1760).[9] Under the saintly influence of the Ba‘al Shem Tov (acronym: the Besht) and his charismatic disciples, almost half of central and eastern Europe’s Jewry had become Hasidim by the early 19th century. The Hasidim—with their ecstatically joyful, spontaneous sacred dancing, their emphasis on mystical experience over dry Talmudic scholarship, and their special devotional focus on the spiritual leader (the tzaddiq) as channel of G-d’s grace (shefa)—were considered excessively “liberal” in the first several generations of the movement, and harassed and even excommunicated by Orthodox Jewish rabbis. It is ironic, then, that in the 20th/21st centuries the Hasidim, who now constitute only about 6% of the world’s 16 million Jews, appear quite conservative. The joyful dancing and experiential emphasis still characterize Hasidic congregations. But—when compared to the liberal Reform and Conservative branches of Judaism in America and Europe, strongly influenced by the European Enlightenment and assimilating modern forms of worship, dress, and lifestyle—the Hasidim seem very much a throwback to the “Old World” of another era. By far the most popular lineage of Hasidism in North America, in fact the world’s most influential Hasidic sect, is the growing, ultra-Orthodox missionary Lubavitcher or Habad movement. Headquartered in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, Habad hosts a population there of some 30,000 souls and includes 500,000 to 700,000 Jews worldwide. This fervent form of mysticism was brought to America in 1940 by Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneerson (1880-1950), who was the leading rabbi in Russia after Sovietization, and whose arrival in New York ushered in a rebirth of Hasidism in the New World. Joseph’s son, the late Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-94) enjoyed immense esteem—“his life was full of miracles.” Veneration attained such levels that more extreme members of his community began to propagate the idea that he was the Mashiach or Messiah. Rabbi Schneerson affirmed it. Alas, not having any children, he left no clear-cut successor; hence, with the passing of this illustrious leader, Habad has lost some momentum until a charismatic new rebbe can be found to replace him. Many aren’t sure this will happen, due to the intense messianism. As it currently stands, a major divide exists between the messianic and “anti-messianic” Lubavitchers, many of the latter having become “ex-Lubavitchers.” (See the excellent xlubi.com website of a former Lubavitcher, the Habad scholar Max Ariel Kohanzad, who has revealed just how profoundly nondual are the teachings of Rebbe Schneerson.) [10] Nevertheless, the influence of Lubavitcher Hasidism has served, and will continue to serve, as a stimulus that indirectly strengthens the several other already flourishing Hasidic lineages. Other Hasidic sects survived the Nazi destruction (many did not) and now exist in Israel, Europe and/or America. They include the Rabinowicz-Monastritsh line descended from Jacob Isaac Rainowicz (d. 1814); the Chernobyl line, from Mordecai Twersky (d. 1837, son of Menahem Nahum); Bobover Hasidism, saved and carried to the US and Israel by Rabbi Solomin Halberstam (1908-2000); Satmar Hasidism, created by Moshe Teitelbaum and carried on by his controversial, anti-Zionist son Yo’el/Joel Teitelbaum (1887-1979); and the most progressive, accessible Hasidic sect, Bratslav Hasidism, started by Nachman of Bratslav (1772-1810), great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov through his holy daughter Adel, and still considered the chief rebbe of that line (this same situation will likely occur in Habad).[11] All sects of Hasidism can remind Jews and other religious people of the beauty of the deeply mystical life focused on G-d as the transcendent ‘Ein Sof and immanent Shekhinah. God manifests as Light, Love, Wisdom (Hochmah), Intelligence (Binah), and all other sefirot-aspects of Divine majesty. Hasidism challenges us to remember that, truly, “There is no place empty of Him,” and that our greatest purpose is serving G-d’s creatures, visualizing the neshâmah or Divine spark within them returning to G-d in all glory in its highest nature as the yechidah or Absolute Spirit. Ultimately we, too, are returned to the sublime state of spiritual union with G-d.

Endnotes 1 “Meditation Grows in Popularity Among Jews,” Religion News Service, Jan. 30, 1993. 2 A fine article on Ayin and Ein Sof is Daniel Matt, “Ayin: The Concept of Nothingness in Jewish Mysticism,” in Robert Forman (Ed.), The Problem of Pure Consciousness: Mysticism and Philosophy, Oxford, 1990, pp. 121-159. On the merkava “throne of God,” see “Throne of God” in Geoffrey Wigoder (Ed. in Chief), The Encyclopedia of Judaism, Macmillan, 1989, pp. 704-5. 3 A large number of books have been published on various texts and aspects of the Kabbalah system and Jewish mysticism. See works by the father of scholarly Kabbalah studies, Gershom Scholem, including Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, NY: Schocken, 1955, On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism (R. Manheim, Tr.), Schocken, 1969, Origins of the Kabbalah (R.J. Werblowsky, Ed., Allan Arkush, Tr.), Princeton Univ., 1990, On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead: Basic Concepts in the Kabbalah, Schocken, 1991, On the Possibility of Jewish Mysticism in Our Time (Jonathan Chapman, Tr.), NY: Jewish Publ. Soc., 1994, G. Scholem (Ed.), Zohar: The Book of Splendor: Basic Readings from the Kabbalah, Schocken, 1987. See Eliezer Schweid, Judaism & Mysticism According to Gershom Scholem: A Critical Analysis & Programmatic Discussion, Decatur, GA: Scholars Press, 1985. See a fine anthology, Daniel Matt, The Essential Kabbalah: The Heart of Jewish Mysticism, HarperCollins, 1995, and Matt (Ed. & Tr.) Zohar: The Book of Enlightenment, Paulist Press, 1988. Other works on Kabbalah/Jewish mysticism include Joseph Dan, Jewish Mysticism (4 vols.), Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1998; J. Dan & Ronald Kiener (Eds.), The Early Kabbalah, Paulist, 1986; Moshe Idel, Kabbalah: New Perspectives, Yale U., 1990; Studies in Ecstatic Kabbalah, SUNY, 1988; Mark Verman, The Books of Contemplative Medieval Jewish Mystical Sources, SUNY, 1992; Aryeh Kaplan, Immortality, Resurrection and the Age of the Universe: A Kabbalistic View, Hoboken, NJ: KTAV, 1994; Meditation and Kabbalah, S. Weiser ed, 1986/1982; The Bahir, Weiser ed., 1989/1980; Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Creation), Weiser ed., 1993/1990; Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi, Kabbalah: Tradition of Hidden Knowledge, London: Thames Hudson, 1980 (illus.); Introduction to the Cabala, Weiser rev. ed., 1991; The Way of Kabbalah, Weiser ed., 1991 (first publ. in 1976); The Work of the Kabbalist, Weiser, 1985; Psychology and Kabbalah, Weiser ed., 1987; Yechiel Bar Lev, An Introduction to Kabbalah, Spring Valley, NY: Feldheim, 1994; David Ariel, The Mystic Quest: An Introduction to Jewish Mysticism, Pantheon, 1992; Moshe Hallamish, An Introduction to Kaballah, SUNY, 1999; Charles Fielding, The Practical Qabalah, Weiser, 1989; Leonard Glotzer, Fundamentals of Jewish Mysticism, Aronson, 1992; Howard Schwartz, Gabriel’s Palace: Jewish Mystical Tales, Aronson, 1994; Perle Besserman (Ed.), Teachings of the Jewish Mystics, Shambhala, 1998; Dan Cohn-Sherbok, Jewish Mysticism: An Anthology, Oxford: One World, 1995; Avram Davis & Manuela Dunn Mascetti, Judaic Mysticism, NY: Hyperion, 1997. 4 The Israel survey was by Maariv newspaper, reported in “One out of five Israelis visit seers,” from news agency C-afp@clari.net (AFP), on the clari.news.religion newswire, Sep. 18, 1997. On Kabbalah in the West, see David Van Biema, “Pop Goes the Kabbalah,” Time, Nov. 24, 1997. 5 On the Jewish connection with Eastern religion, specifically Zen, see Harold Heifetz (Ed.), Zen and Hasidism, Wheaton, IL: Quest, 1978. 6 On Hasidic belief in reincarnation, see interesting works by Yonassan Gershom, Beyond the Ashes: Cases of Reincarnation from the Holocaust (Jon Robertson, Ed.), Virginia Beach, VA: A.R.E. (Assoc. for Research and Enlightenment) Press, 1992; From Ashes to Healing: Mystical Encounters with the Holocaust, A.R.E., 1996. Gershom relates cases of Jews and non-Jews with clear memories of previous lives under Nazi persecution. 7 Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Shohama Harris Wiener & Jonathan Omer-Man, Worlds of Jewish Prayer: A Festschrift in Honor of Rabbi Zalman M. Schachter-Shalomi, Jason Aronson, 1994; Z. Schachter & Edward Hoffman, Sparks of Light, Shambhala, 1983; Z. Schachter-Shalomi & Donald Gropman, The First Step, Bantam, 1983. See the periodical of the P’nai Or, New Menorah (6723 Emlen St., Philadelphia, PA 19119); Joseph Gelberman, To Be... Fully Alive, Farmingdale, NY: Coleman Graphics, 1983, Reaching a Mystical Experience: A Kabbalistic Encounter, NY: Wisdom Press, 1970, and the journal of the Little Synagogue, Kabbalah for Today (155 E. 22nd St., N.Y., NY 10010); David Cooper, God Is A Verb: God and the Practice of Mystical Kabbalah, Riverhead, 1997; Rodger Kamenetz, Stalking Elijah: Adventures with Today’s Jewish Mystical Masters, HarperSF, 1997. 8 On this controversy, see Rabbis Zalman Schachter and Chaim Tsvi Hollander in H. Heifetz (Ed.), Zen and Hasidism, op. cit., pp. 135-60. 9 On Hasidism (English language): Gershon David Hundert, Essential Papers on Hasidism: Origins to Present, NYU Press, 1991; Moshe Rosman, Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Ba‘al Shem Tov, UC Press, 1996; Dan Ben-Amos & Jerome Mintz (Eds.), In Praise of the Baal Shem Tov: The Earliest Collection of Legends About the Founder of Hasidism, Bloomington, IN: Indiana U., 1970; Abraham Heschel, The Circle of the Ba‘al Shem Tov: Studies in Hasidism (S.H. Dresner, Ed.), U of Chicago, 1985; Avraham Yaakov Finkel, The Great Chasidic Masters, Aronson, 1992; Aryeh Kaplan, The Light Beyond: Adventures in Hassidic Thought, Brooklyn, NY: Maznaim, 1981, and Chasidic Masters and Their Teachings, Maznaim, 1984; Harry Rabinowicz, Hasidism: The Movement and Its Masters, Aronson, 1988; Moshe Idel, Hasidism: Between Ecstasy and Magic, SUNY, 1995; Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, Schocken, 1954, pp. 325-350, The Messianic Idea in Judaism and Other Essays on Jewish Spirituality, Schocken, 1971, pp. 176-250; Joseph Dan, The Teachings of Hasidism, NY: Behrman, 1983; Elie Wiesel, Souls on Fire: Portraits and Legends of Hasidic Masters, Random House, 1972; Martin Buber, Tales of the Hasidim (Olga Marx, Tr.) (2 vols.), Schocken, 1947-8; M. Buber, Hasidism and Modern Man (M. Friedman, Ed. & Trans.), Harper, 1966 (first pub. 1958); Samuel Dresner, The Zaddik, London, 1960; Jiri Langer, Nine Gates to the Chassidic Mysteries (Stephen Jolly, Tr.), Behrman, 1976; Louis Jacobs, Hasidic Prayer, Washington: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1978, and Jewish Mystical Testimonies, NY, 1987; Arthur Green (Ed.), Your Word Is Fire: The Hasidic Masters on Contemplative Prayer, Jewish Lights Publ., 1993; Rachel Elior, The Paradoxical Ascent, SUNY, 1993; Gedalyah Nigal, Magic, Mysticism and Hasidism: the Supernatural in Jewish Thought, Aronson, 1994; Norman Lamm, The Religious Thought of Hasidism, Text and Commentary, NJ: Michael Scharf Publ. Trust of Yeshiva Univ., 1999; Herbert Weiner, 9½ Mystics: The Kabbala Today, NY: Collier, 1969. Fine articles include Joseph Dan, “Hasidism: An Overview,” in Mircea Eliade (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Religion, NY: Macmillan, 1987, Vol. 6, pp. 204-211; Arthur Green, “Hasidism” (and “Spirituality”) in A. Cohen & Paul Mendes-Florher (Eds.), Contemporary Jewish Thought: Original Essays on Critical Concepts, Movements, and Beliefs, Free Press, 1988; and the various articles on Hasidism and Jewish mysticism in Arthur Green (Ed.), Jewish Spirituality II: From the Sixteenth Century Revival to the Present, Crossroad, 1987 (see also A. Green, Ehyeh: A Kabbalah for Tomorrow, Jewish Lights, 2004). Other good works on modern-era Hasidism are Avraham Yaakov Finkel, Contemporary Sages: The Great Chasidic Masters of the Twentieth Century, Aronson, 1994; Menachem Daum & Oren Rudavsky, A Life Apart: Hasidism in America, 1997 [based on their documentary film]; Robert Eisenberg, Boychiks in the Hood: Travels in the Hasidic Underground, HarperSF, 1995; David Landau, Piety and Power: The World of Jewish Fundamentalism, NY: Hill & Wang, 1993 (examines Hasidism and other ultra-Orthodox Haredi Jewish groups and Israeli politics). 10 On Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (Schneersohn), see the many obituaries appearing in the press on June 13, 1994 and after; Shaul Shimon Deutsch, Larger than Life: The Life & Times of the Lubavitcher Rebbe Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (2 vols.), NY: Chasidic Historical Prods., 1997; Eliyahu & Malka Touger, To Know and to Care: An Anthology of Chassidic Stories about the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, NY: Sichos In English, 1994; Chaim Calfin, Conversations with the Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, LA: JEC Publ., 1996. On English-language editions of his teachings, see M.M. Schneersohn, Toward a Meaningful Life: The Wisdom of the Rebbe (S. Jacobson, Ed.), Morrow, 1995; Letters by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Brooklyn, NY: Kehot Publ. Society, 1979; On the Essence of Chassidus (R.Y.H Greenberg & S.S Handelman, Tr.), Kehot, 1986, and other books, as well as the journal Talks and Tales (770 Eastern Pkwy, Brooklyn, NY 11213). See a large, annotated bibliography at xlubi.com/x5pbibliog.htm, and linked articles by Max Ariel Kohanzad on Schneersohn’s profoundly nondual theology; on this, see Rabbi Faitel Levin, Heaven On Earth: Reflections on the Theology of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Kehot, 2000. Two books relating the Rebbe’s ideas to Eastern spirituality are Gutman Locks, There is One, publ. by author (24 Chabad St., Old City, Jerusalem), 1993; The Raging Mind, 2000. On Lubavitcher Habad Hasidism, see the main work of its founder, Rabbi Shne’ur Zalman (1754-1813), Tanya’, Kehot, 1956; Gershon Kranzler, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Ladi [sic]: A Brief Presentation of the Life, Work and Basic Teachings of the Founder of Chabad Chassidism (based on talks with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem. M. Schneerson), Kehot, 1974; Nissan Mindel, The Philosophy of Habad, Kehot, 1973; many works by Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn (1880-1950), all published by Kehot; Yehudah Chitrik, From My Fathers Table: A Treasury of Chabad Chassidic Stories (E. Touger, Tr.), Jerusalem: Vagshal, 1991; Louis Jacob, Seeker of Unity, NY, 1966; Herbert Weiner, 9½ Mystics: The Kabbala Today, Ch. 6; and Noson Gurary, The Thirteen Principles of Faith: A Chasidic Viewpoint, Aronson, 1996. 11 On Rabbi Nachman, see Arthur Green, Tormented Master: The Life and Spiritual Quest of Rebbe Nahman of Bratslav, Jewish Lights Publ., 1992/1979; Arnold Band, Nahman of Bratslav: The Tales, Paulist, 1978; on the web, see www.breslov.org.

|